Many of you got upset when I mentioned the possibility that parents use smart phone software to control the social media usage of their kids. There was an outcry about how badly those systems work (is that endogenous?). But that is missing the point.

If you wish to limit social media usage, mandate that the phone companies install such software and make it more effective. Or better yet commission or produce a public sector app to do the same, a “public option” so to speak. Parents can then download such an app on the phone of their children, or purchase the phone with the app, and manipulate it as they see fit.

If you do not think government is capable of doing that, why think they are capable of running an effective ban for users under the age of sixteen? Maybe those apps can be hacked but we all know the “no fifteen year olds” solution can be hacked too, for instance by VPNs or by having older friends set up the account.

My proposal has several big advantages:

1. It keeps social media policy in the hands of the parents and away from the government.

2. It does not run the risk of requiring age verification for all users, thus possibly banishing anonymous writing from the internet.

3. The government does not have to decide what constitutes a “social media site.”

Just have the government commission a software app that can give parents the control they really might want to have. I am not myself convinced by the market failure charges here, but I am very willing to allow a public option to enter the market.

The fact that this option occasions so little interest from the banners I find highly indicative.

The post Think through the situation one step further appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

Iran is slowly emerging from the most severe communications blackout in its history and one of the longest in the world. Triggered as part of January’s government crackdown against citizen protests nationwide, the regime implemented an internet shutdown that transcends the standard definition of internet censorship. This was not merely blocking social media or foreign websites; it was a total communications shutdown.

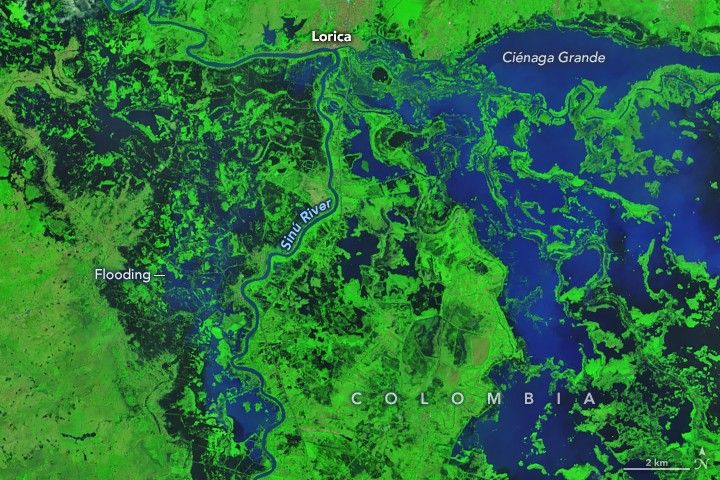

Unlike previous Iranian internet shutdowns where Iran’s domestic intranet—the National Information Network (NIN)—remained functional to keep the banking and administrative sectors running, the 2026 blackout disrupted local infrastructure as well. Mobile networks, text messaging services, and landlines were disabled—even Starlink was blocked. And when a few domestic services became available, the state surgically removed social features, such as comment sections on news sites and chat boxes in online marketplaces. The objective seems clear. The Iranian government aimed to atomize the population, preventing not just the flow of information out of the country but the coordination of any activity within it.

This escalation marks a strategic shift from the shutdown observed during the “12-Day War” with Israel in mid-2025. Then, the government primarily blocked particular types of traffic while leaving the underlying internet remaining available. The regime’s actions this year entailed a more brute-force approach to internet censorship, where both the physical and logical layers of connectivity were dismantled.

The ability to disconnect a population is a feature of modern authoritarian network design. When a government treats connectivity as a faucet it can turn off at will, it asserts that the right to speak, assemble, and access information is revocable. The human right to the internet is not just about bandwidth; it is about the right to exist within the modern public square. Iran’s actions deny its citizens this existence, reducing them to subjects who can be silenced—and authoritarian governments elsewhere are taking note.

The current blackout is not an isolated panic reaction but a stress test for a long-term strategy, say advocacy groups—a two-tiered or “class-based” internet known as Internet-e-Tabaqati. Iran’s Supreme Council of Cyberspace, the country’s highest internet policy body, has been laying the legal and technical groundwork for this since 2009.

In July 2025, the council passed a regulation formally institutionalizing a two-tiered hierarchy. Under this system, access to the global internet is no longer a default for citizens, but instead a privilege granted based on loyalty and professional necessity. The implementation includes such things as “white SIM cards“: special mobile lines issued to government officials, security forces, and approved journalists that bypass the state’s filtering apparatus entirely.

While ordinary Iranians are forced to navigate a maze of unstable VPNs and blocked ports, holders of white SIMs enjoy unrestricted access to Instagram, Telegram, and WhatsApp. This tiered access is further enforced through whitelisting at the data center level, creating a digital apartheid where connectivity is a reward for compliance. The regime’s goal is to make the cost of a general shutdown manageable by ensuring that the state and its loyalists remain connected while plunging the public into darkness. (In the latest shutdown, for instance, white SIM holders regained connectivity earlier than the general population.)

The technical architecture of Iran’s shutdown reveals its primary purpose: social control through isolation. Over the years, the regime has learned that simple censorship—blocking specific URLs—is insufficient against a tech-savvy population armed with circumvention tools. The answer instead has been to build a “sovereign” network structure that allows for granular control.

By disabling local communication channels, the state prevents the “swarm” dynamics of modern unrest, where small protests coalesce into large movements through real-time coordination. In this way, the shutdown breaks the psychological momentum of the protests. The blocking of chat functions in nonpolitical apps (like ridesharing or shopping platforms) illustrates the regime’s paranoia: Any channel that allows two people to exchange text is seen as a threat.

The United Nations and various international bodies have increasingly recognized internet access as an enabler of other fundamental human rights. In the context of Iran, the internet is the only independent witness to history. By severing it, the regime creates a zone of impunity where atrocities can be committed without immediate consequence.

Iran’s digital repression model is distinct from, and in some ways more dangerous than, China’s “Great Firewall.” China built its digital ecosystem from the ground up with sovereignty in mind, creating domestic alternatives like WeChat and Weibo that it fully controls. Iran, by contrast, is building its controls on top of the standard global internet infrastructure.

Unlike China’s censorship regime, Iran’s overlay model is highly exportable. It demonstrates to other authoritarian regimes that they can still achieve high levels of control by retrofitting their existing networks. We are already seeing signs of “authoritarian learning,” where techniques tested in Tehran are being studied by regimes in unstable democracies and dictatorships alike. The most recent shutdown in Afghanistan, for example, was more sophisticated than previous ones. If Iran succeeds in normalizing tiered access to the internet, we can expect to see similar white SIM policies and tiered access models proliferate globally.

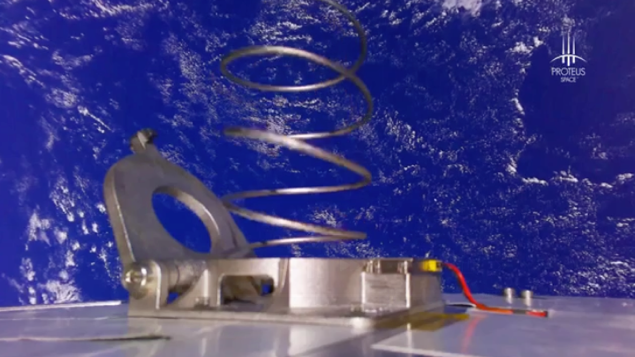

The international community must move beyond condemnation and treat connectivity as a humanitarian imperative. A coalition of civil society organizations has already launched a campaign calling for “direct-to-cell” (D2C) satellite connectivity. Unlike traditional satellite internet, which requires conspicuous and expensive dishes such as Starlink terminals, D2C technology connects directly to standard smartphones and is much more resilient to infrastructure shutdowns. The technology works; all it requires is implementation.

This is a technological measure, but it has a strong policy component as well. Regulators should require satellite providers to include humanitarian access protocols in their licensing, ensuring that services can be activated for civilians in designated crisis zones. Governments, particularly the United States, should ensure that technology sanctions do not inadvertently block the hardware and software needed to circumvent censorship. General licenses should be expanded to cover satellite connectivity explicitly. And funding should be directed toward technologies that are harder to whitelist or block, such as mesh networks and D2C solutions that bypass the choke points of state-controlled ISPs.

Deliberate internet shutdowns are commonplace throughout the world. The 2026 shutdown in Iran is a glimpse into a fractured internet. If we are to end countries’ ability to limit access to the rest of the world for their populations, we need to build resolute architectures. They don’t solve the problem, but they do give people in repressive countries a fighting chance.

This essay originally appeared in Foreign Policy.

NASA announced major changes to its Artemis lunar architecture, adding a test flight of lunar landers in low Earth orbit while canceling planned upgrades to the Space Launch System.

The post NASA revises plans for future Artemis missions, cancels upgrades to SLS appeared first on SpaceNews.

The failure of a propellant tank during testing in January will delay the first launch of Rocket Lab’s Neutron rocket to at least the fourth quarter of this year.

The post Rocket Lab delays Neutron debut to late 2026 appeared first on SpaceNews.

China will begin its first one-year duration astronaut mission this year, while the first international astronaut will make a short visit to Tiangong space station.

The post China set for its first one-year human spaceflight mission, confirms Pakistani astronaut flight appeared first on SpaceNews.

Peru has increased its squid catch limit. The article says “giant squid,” but they can’t possibly mean that.

As usual, you can also use this squid post to talk about the security stories in the news that I haven’t covered.

Although I’m optimistic that AI will design better drug candidates, this alone cannot ensure “therapeutic abundance,” for a few reasons. First, because the history of drug development shows that even when strong preclinical models exist for a condition, like osteoporosis, the high costs needed to move a drug through trials deters investment — especially for chronic diseases requiring large cohorts. And second, because there is a feedback problem between drug development and clinical trials. In order for AI to generate high-quality drug candidates, it must first be trained on rich, human data; especially from early, small-n studies.

…Recruiting 1000 patients across 10 sites takes time; understanding and satisfying unclear regulatory requirements is onerous and often frustrating; and shipping temperature-sensitive vials to research hospitals across multiple states takes both time and money.

…For many diseases, however, the relevant endpoints take a very long time to observe. This is especially true for chronic conditions, which develop and progress over years or decades. The outcomes that matter most — such as disability, organ failure, or death — take a long time to measure in clinical trials. Aging represents the most extreme case. Demonstrating an effect on mortality or durable healthspan would require following large numbers of patients for decades. The resulting trial sizes and durations are enormous, making studies extraordinarily expensive. This scale has been a major deterrent to investment in therapies that target aging directly.

Here is more from Asimov Press and Ruxandra Teslo.

The post AI Won’t Automatically Accelerate Clinical Trials appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

Financial responsibility often carries meaning beyond the individual. Supporting family, building stability, investing wisely, and planning for the future are values deeply embedded in many households. Yet rising living costs, market volatility, student loans, mortgages, and everyday expenses have created new forms of financial tension.

In this environment, digital gambling platforms have become part of the broader economic landscape. Online betting, interactive slot rooms, live dealer tables, and competitive welcome bonuses are no longer niche entertainment. They are integrated into mobile culture, streaming media, and everyday financial conversations.

Understanding how financial pressure interacts with iGaming is not about blame. It is about clarity.

The modern U.S. economy is defined by speed. Payments move instantly. Investments shift in seconds. Entertainment is on demand. Gambling platforms mirror that structure.

A modest deposit can activate a matched bonus. A few calculated wagers can create short-term momentum. For players navigating tight budgets, that possibility can feel empowering.

This is where financial pressure becomes economically relevant. Tension increases attention. Attention drives engagement. Engagement fuels platform revenue.

That dynamic does not automatically imply harm. It simply highlights how expectation and probability intersect.

For Greek American players who value strategic thinking, the key question becomes: how do you participate without allowing financial stress to dictate decisions?

Education changes outcomes. That is where streaming-based aggregators enter the picture.

A comparison hub such as slothub34.com does not operate gambling services or issue promotional credits. Instead, it provides structured visibility into casino bonuses, betting incentives, slot mechanics, live dealer formats, and wagering conditions across multiple operators. Streamers demonstrate real-time gameplay sessions, volatility patterns, bonus triggers, and bankroll movement, allowing viewers to see how platforms function before depositing funds.

This model serves a practical purpose. It reduces reliance on marketing language and increases exposure to actual gameplay behavior. When viewers observe how welcome offers interact with wagering requirements or how different betting environments affect balance swings, they gain context.

Financial pressure loses influence when information increases.

Licensed online casinos design their ecosystems carefully. Welcome packages, reload incentives, and loyalty rewards are structured to encourage participation while maintaining profitability.

When a platform like SlotsHub Skills Casino promotes competitive betting bonuses tied to slot participation or table wagering credits, it highlights opportunity. For experienced players, such offers can extend playtime and provide strategic flexibility. The value depends on the rollover structure, maximum wager limits during bonus use, and withdrawal policies.

Understanding these mechanics matters. A promotion is not free capital; it is conditional leverage.

The difference between entertainment and financial strain often comes down to how clearly those conditions are understood before play begins.

Beyond bonus structures, gameplay behavior itself reveals important insights.

Within streamed review sessions of platforms such as SlotsHub Skills Casino, attention shifts from advertising to actual performance. Viewers can observe how volatility impacts balance fluctuations, how often special features activate, and how session pacing influences bankroll sustainability.

This transparency reframes risk. Instead of imagining potential outcomes, players see statistical behavior unfold in real time. That exposure encourages more disciplined expectations.

For members of the Greek community in the U.S., who often approach business decisions analytically, this format aligns with familiar principles: research first, commit second.

Financial pressure amplifies uncertainty. Clear answers reduce it.

Short-term gains are possible, but consistent long-term income is statistically unlikely for casual participants. Online wagering is built around probability models that favor the operator over time. Treating it as entertainment rather than income strategy protects financial stability.

Focus on effective value, not headline percentages. Examine wagering multipliers, eligible titles, time limits, and withdrawal caps. A smaller, transparent offer may provide more realistic utility than a large bonus with restrictive terms.

Set fixed deposit limits before logging in. Separate entertainment funds from essential living expenses. Use cooling-off tools when available. Avoid increasing bet size to recover losses. Financial discipline should remain independent of session results.

Financial tension is a reality in modern America. It influences investment decisions, career moves, and consumption habits. In digital gambling environments, that same pressure can increase emotional participation.

However, information shifts the equation.

Streaming comparison platforms create distance between marketing promise and actual structure. Players who observe mechanics, compare wagering terms, and evaluate multiple operators gain perspective. They replace urgency with analysis.

Financial pressure does not need to become a revenue engine for impulsive decisions. With structured research, controlled budgeting, and clear expectations, participation in online betting environments can remain what it is designed to be: regulated digital entertainment.

For Greek American players navigating opportunity in the United States, the advantage has always been knowledge, discipline, and community conversation. Those principles apply online as much as anywhere else.

CLICK HERE TO DONATE IN SUPPORT OF DCREPORT’S NONPROFIT NEWSROOM

The post Financial Pressure as a Revenue Engine appeared first on DCReport.org.

Across generations, financial discipline has been treated not merely as a habit, but as a core value. Traditions of business ownership, careful investment, and strategic decision-making highlight a deep awareness of risk and reward. At the same time, modern digital environments introduce subtle influences that operate below conscious awareness.

Online gambling platforms, live dealer rooms, slot interfaces, and competitive welcome bonuses are not only forms of entertainment. They are structured ecosystems shaped by behavioral economics.

Understanding how temptation works in iGaming is not about fear. It is about awareness.

Behavioral economics teaches us that people do not always make purely rational choices. Decisions are shaped by context, presentation, timing, and emotional triggers.

In digital betting environments, several factors interact at once:

These mechanics are not accidental. They are part of a design strategy built to sustain engagement.

For Greek players in the USA comparing platforms, recognizing these patterns changes the experience. Instead of reacting emotionally to a headline offer, they can evaluate structure.

A streaming-based comparison hub such as slothub33.com provides visibility into real casino bonuses, betting incentives, slot volatility, live dealer formats, and wagering conditions across multiple operators. Rather than operating a gambling service directly, the platform allows viewers to watch real-time sessions, observe bonus triggers, and analyze how bankroll movement unfolds during actual gameplay.

Seeing mechanics in action reduces guesswork.

One of the strongest behavioral drivers in gambling environments is the near-miss effect. When a slot display shows two matching symbols and the third lands just above the payline, the brain processes it differently from a total loss. Research in behavioral psychology shows that near-misses activate reward-related neural pathways, even though the financial outcome is the same as any other non-winning spin.

This mechanism keeps attention engaged.

When players watch streamed sessions reviewing platforms such as SlotsHub Live Skillz Casino and its slot-based betting promotions or table wagering bonuses, they can observe how often bonus features activate and how frequently near-miss patterns appear. Real-time demonstration provides context that static advertising cannot.

For disciplined players, context reduces emotional bias.

Another core principle of behavioral economics is variable reinforcement. When outcomes are unpredictable but potentially rewarding, engagement increases. This is the same principle that drives social media notifications and investment speculation.

In online gambling, unpredictable payouts combined with fast play cycles create momentum. A small win resets confidence. A bonus round extends session time. A reload offer arrives at the right psychological moment.

Financial pressure can amplify these effects. Rising living costs in the United States — housing, insurance, healthcare, and education — create stress. Under stress, people often seek opportunities that promise change.

The key distinction is between structured entertainment and financial expectation.

Greek American players, known for approaching opportunity strategically, benefit from separating these categories clearly.

Welcome packages and promotional incentives can be valuable tools when understood properly. A deposit match tied to slot participation or betting credits may increase playtime and exploration. But behavioral economics warns about framing effects.

A 100% bonus sounds like “extra money.” In reality, it is conditional credit governed by rollover requirements and time restrictions.

When reviewing operators like SlotsHub Live Skillz Casino and its competitive welcome offers connected to slot wagering or live table action, experienced users analyze effective value rather than headline size. Streamed breakdowns of terms and conditions reveal whether an offer realistically aligns with player strategy.

Clarity weakens temptation.

Temptation becomes manageable when questions are addressed directly.

It does not change probability, but it improves expectation management. Observing volatility levels and bonus frequency helps players choose formats aligned with their risk tolerance.

Not necessarily. A moderate incentive with transparent rollover rules may be more practical than a large offer with restrictive wagering multiples. Comparison research reduces impulsive deposits.

Set fixed deposit and loss limits before starting. Avoid increasing bet size after consecutive losses. Treat each session as pre-budgeted entertainment, not income recovery.

Behavioral economics does not suggest that players lack discipline. It shows that environment shapes behavior.

Online gambling platforms are carefully engineered digital systems. Fast registration, seamless payment processing, personalized incentives, and visual reinforcement are designed to sustain activity.

Streaming comparison platforms introduce balance. By observing multiple operators, analyzing slot volatility, reviewing live dealer pacing, and comparing bonus conditions across the market, players gain distance from impulse.

For the Greek community in the United States, where entrepreneurship and calculated risk-taking are cultural strengths, awareness becomes an advantage.

Temptation does not disappear. But when mechanics are visible, probabilities understood, and budgets controlled, participation becomes intentional rather than reactive.

Behavioral economics explains why digital betting environments are compelling. Informed comparison and disciplined budgeting determine whether that pull becomes entertainment or financial strain.

CLICK HERE TO DONATE IN SUPPORT OF DCREPORT’S NONPROFIT NEWSROOM

The post Behavioral Economics of Temptation appeared first on DCReport.org.

In a digital economy built on speed and stimulation, attention has become one of the most valuable assets. Every modern platform competes for it — streaming services, trading apps, social networks, and online gambling environments alike. In environments where financial discipline and strategic thinking serve as guiding principles, understanding how attention functions within digital betting spaces becomes less a choice and more a necessity.

One of the most influential psychological forces shaping online gambling behavior is the near-miss effect.

A near-miss happens when the outcome appears just short of success. Two jackpot symbols align. The third stops one position away. A bonus feature animation builds tension before narrowly missing activation.

Mathematically, the result is identical to any other non-winning round. Psychologically, it is not.

Behavioral research shows that near-misses stimulate parts of the brain associated with reward processing. Instead of discouraging continuation, they often increase motivation. The mind interprets the event as proximity to success rather than as loss.

In digital slot environments and live betting formats at WinAirlines Casino, immersive graphics, rapid spin cycles, and layered bonus structures amplify that sensation. The experience feels dynamic and forward-moving, even when outcomes remain governed by probability.

Understanding that distinction is critical.

Online gambling platforms are designed around short feedback loops. Spin. Result. Animation. Reset. The pace is intentional. Fast cycles maintain engagement and minimize interruption.

This rhythm mirrors the broader attention economy. The shorter the cycle, the stronger the immersion. When near-miss patterns are integrated into that rhythm, emotional continuity deepens.

Players exploring winairlines-gr.com, where casino bonuses, wagering formats, slot libraries, and live dealer environments are presented in a seamless digital interface, enter a space optimized for engagement. Competitive welcome offers and structured promotional incentives add another layer of momentum.

The system is not random chaos. It is structured design.

Another principle closely tied to the near-miss effect is variable reinforcement. When rewards arrive unpredictably, participation intensifies. This is the same mechanism that drives engagement in financial markets and social platforms.

In online betting, unpredictability is part of the core experience. A small win resets confidence. A bonus round extends session time. A narrow miss sustains anticipation. Each outcome feeds the next decision.

At WinAirlines Casino, structured betting incentives and promotional bonuses tied to slot participation or live table action can extend early sessions. When approached with planning and clear budgeting, these tools enhance entertainment value. Without structure, however, emotional interpretation can replace rational analysis.

For many in the Greek American community, separating emotion from calculation is second nature in business and investment. Applying that same discipline inside digital gambling environments transforms the experience.

The most important insight from behavioral economics is simple: environment shapes perception. Interfaces guide focus. Sound design reinforces outcomes. Visual animation amplifies anticipation.

But awareness restores balance.

Recognizing that a near-miss is not progress but probability prevents misinterpretation. Understanding volatility levels clarifies why outcomes fluctuate. Observing session pacing reveals how quickly bankroll movement can accelerate.

Online gambling platforms operate within a competitive and regulated U.S. market. Their goal is engagement. The player’s goal should be clarity.

For Greek Americans navigating opportunity in the United States, advantage has always come from preparation, research, and measured risk-taking. The same principle applies here. When attention is consciously managed, participation becomes intentional rather than reactive.

The near-miss effect explains why certain moments feel powerful. The attention economy explains why they feel immediate. Informed players understand both — and choose their pace accordingly.

CLICK HERE TO DONATE IN SUPPORT OF DCREPORT’S NONPROFIT NEWSROOM

The post The Near-Miss Effect and the Attention Economy appeared first on DCReport.org.

For players originally from the United Kingdom who now live in the United States, gambling has always carried a dual identity. It is entertainment, but it is also mathematics. Whether it is a weekend wager, a spin on a digital reel, or a live dealer session, every decision sits somewhere between excitement and calculation.

In today’s regulated online environment, understanding that balance is no longer optional. It is essential.

Online platforms combine advanced software, probability structures, and immersive design to create engaging experiences. But beneath the visuals and promotional banners lies a consistent truth: every outcome is governed by mathematical models. The difference between enjoyment and frustration often comes down to how well players understand that structure.

At the core of every online gambling environment is probability. Slot outcomes are determined by random number generators. Table formats operate within fixed statistical frameworks. Long-term returns are calculated through defined payout percentages, often referred to as RTP (Return to Player).

Short-term results can vary dramatically. A player may experience a profitable session within minutes. Another may encounter a losing streak despite consistent strategy. This variability is not manipulation; it is variance.

Variance creates the perception of opportunity. It also creates the illusion of patterns where none exist.

For UK-born players accustomed to the structured and regulated gambling culture of Britain, adapting to the U.S. online environment means recognizing how these same principles apply digitally. Probability does not change based on geography. The mathematics remains constant.

If chance defines the framework, calculation defines control.

Calculation in online gambling is not about predicting outcomes. It is about managing exposure. This includes:

When exploring platforms such as rock-star-casino.com, where competitive casino bonuses, wagering opportunities, slot titles, and live dealer formats are presented within a streamlined interface, players benefit from approaching each offer analytically. A generous welcome promotion may extend playtime, but only if the rollover structure is clearly understood.

Calculation transforms excitement into structured entertainment.

The tension between chance and calculation becomes visible during emotionally charged sessions. A near win may feel like progress. A short streak of success may create overconfidence. Promotional incentives can encourage extended participation.

Within the broader online gambling landscape, platforms like Rockstar Casino and its casino bonuses, betting promotions, and immersive slot experiences provide a dynamic environment. These features are designed to engage players and remain competitive in a regulated market. The responsibility to interpret those features rationally, however, remains with the player.

Understanding house edge, payout percentages, and volatility profiles prevents emotional momentum from overriding discipline.

The goal is not to eliminate excitement. It is to ensure excitement does not dictate financial decisions.

One of the most misunderstood elements in online gambling is volatility. High-volatility formats may produce larger payouts but less frequent wins. Lower-volatility options tend to offer smaller but more consistent returns.

Neither is inherently better. The difference lies in expectation management.

Players who understand volatility are less likely to misinterpret normal statistical swings as signals. In competitive environments like Rockstar Casino, where live dealer wagering and digital reel formats coexist alongside structured promotional offers, knowing how volatility influences session length can prevent unnecessary risk escalation.

Expectation is the foundation of balance.

British gambling culture traditionally emphasizes regulation, transparency, and responsible participation. Living in the United States introduces a faster digital ecosystem, broader state-level regulation differences, and aggressive competition among platforms.

For expatriates navigating both worlds, balance becomes a strategic asset.

The American online gambling market offers convenience, innovation, and accessibility. But speed can amplify decision-making pressure. Fast deposits, quick results, and immediate bonus activation compress the timeline between impulse and action.

Maintaining UK-style discipline within a U.S. digital framework creates stability.

Online gambling is designed to be engaging. Visual effects, loyalty rewards, leaderboard features, and promotional campaigns contribute to immersion. At rock-star-casino.com, structured wagering options, competitive bonus incentives, and diverse gaming formats are part of that experience.

Structured enjoyment means defining limits before logging in. It means understanding that every spin and every hand exists within probability. It means recognizing that long-term profitability is statistically unlikely for casual players.

When chance and calculation operate together, gambling remains entertainment. When calculation disappears, volatility feels unpredictable and stressful.

The balance between chance and calculation is not abstract theory. It is practical behavior.

Chance provides possibility. Calculation provides structure. Together, they define responsible participation.

For UK players living in the USA, combining cultural discipline with digital awareness offers an advantage. Knowledge of probability, awareness of volatility, and careful evaluation of casino bonuses and wagering conditions create clarity.

Online gambling will always contain uncertainty. That is its nature. But uncertainty does not require impulsivity.

When calculation supports chance, the experience becomes controlled, informed, and sustainable.

CLICK HERE TO DONATE IN SUPPORT OF DCREPORT’S NONPROFIT NEWSROOM

The post The Balance Between Chance and Calculation appeared first on DCReport.org.

The pursuit of opportunity is often deeply personal. Building restaurants, shipping businesses, retail shops, and professional careers requires a clear understanding of both risk and reward. In today’s digital environment, that same mindset frequently extends to online betting platforms, interactive slot rooms, live dealer tables, and welcome bonus packages that promise a strong beginning.

The idea feels simple. A reasonable deposit, a competitive match offer, a few well-timed spins, and the possibility of meaningful winnings appears within reach. Yet behind that optimism stands what economists describe as the “economy of hope” — a system where aspiration itself becomes part of the product.

Online gambling platforms are structured to create immediacy. Registration is fast. Payments are streamlined. Promotional credits are activated instantly. Mobile access ensures that wagering fits into busy schedules.

For Greek players in the USA comparing platforms through structured review hubs, the experience becomes even more organized. A trusted comparison source like slothub38.com allows users to evaluate competitive casino bonuses, betting incentives, slot selections, and reward systems in one place. Instead of reacting to marketing headlines, players can examine wagering requirements, payout terms, and loyalty mechanics side by side.

This transparency creates a sense of control. It feels less like guesswork and more like informed decision-making.

At the same time, anticipation remains powerful. Near wins, progressive jackpots, time-sensitive promotions, and leaderboard competitions stimulate excitement. Hope becomes tangible.

Modern online betting environments are carefully designed ecosystems. They combine entertainment, behavioral psychology, and financial structure.

Welcome offers, reload incentives, and VIP programs are central tools used by licensed online casinos to attract and retain players. These promotions can reduce the initial financial commitment and extend playtime — but they always come with specific terms and wagering conditions.

A streaming comparison platform such as slothub38.com does not operate a gambling site or issue bonuses directly. Instead, its role is analytical and observational. Streamers demonstrate slot mechanics, volatility patterns, bonus round structures, and payout behavior in real time, helping viewers understand how different games actually function before committing their own funds.

When reviewing platforms like SlotsHub Casino, experienced players often look beyond headline bonus percentages and evaluate how deposit matches apply to slot play, how wagering credits interact with table betting, and what practical limitations may affect withdrawals. Seeing these mechanics demonstrated live — rather than relying solely on promotional copy — allows players to make more informed decisions.

For many in the Greek American community, this distinction matters. A comparison hub provides visibility and education, not financial promises. It shifts the focus from emotional reaction to structured evaluation.

Unlike traditional gaming venues, digital platforms operate around the clock. A quick spin after work or a live dealer session on a weekend evening is always available.

This accessibility is convenient, particularly for Greek American professionals balancing demanding schedules. But convenience can blur limits. Without predefined boundaries, occasional entertainment can slowly become habitual spending.

The key difference between sustainable play and financial strain often lies in structure.

The regulated U.S. gambling landscape continues to expand across states. For Greek players living in eligible jurisdictions, options are abundant. Each platform promotes attractive features: exclusive slot tournaments, enhanced odds, cashback rewards, and seasonal promotions.

Comparison-driven research changes the equation. Instead of reacting emotionally to a single offer, players can analyze:

Within streaming-based reviews of platforms like SlotsHub Casino, audience attention often shifts away from promotional messaging and toward actual gameplay mechanics. Streamers demonstrate how slot titles behave at different bet levels, how frequently bonus features are triggered, how volatility affects balance swings, and how a bankroll moves during a live session.

This format allows viewers to observe real-time performance rather than rely on marketing descriptions. By comparing multiple operators through structured live sessions, the focus moves from emotional expectation to measurable risk structure and gameplay dynamics.

The belief in quick financial relief rarely appears in isolation. Rising living costs, fluctuating markets, and economic uncertainty influence perception. In periods of financial pressure, the idea that a well-timed wager might create breathing room can feel compelling.

Digital design reinforces that belief. Animated wins, celebratory sounds, dynamic odds displays, and leaderboard rankings stimulate momentum. The interface makes progress feel immediate, even when outcomes remain statistically balanced over time.

Yet sustainable participation requires perspective. Bankroll management, deposit limits, session time caps, and a clear separation between entertainment funds and essential expenses are not optional safeguards — they are foundational.

Online wagering can be engaging and social. It becomes problematic only when hope replaces planning.

When evaluating online betting platforms, comparing casino bonuses, or deciding how much to deposit, several practical concerns tend to surface.

Short-term wins are absolutely possible. Variance can favor the player during specific sessions, especially in lower-volatility slot titles or strategic table play. Over time, however, house edge mechanics apply. For most casual participants, long-term profitability is unlikely. Viewing digital wagering as paid entertainment rather than income generation creates healthier expectations.

They can be valuable if assessed carefully. A well-structured match offer increases playtime and provides room to explore different gaming formats. The real measure of value depends on rollover requirements, eligible titles, and withdrawal restrictions. Comparing detailed terms allows players to determine whether a promotion genuinely aligns with their strategy.

Predefined limits are critical. Setting a fixed entertainment budget before logging in prevents emotional decisions mid-session. Once that amount is reached, stepping away protects both finances and mindset. Many regulated platforms offer deposit limits and cooling-off features that reinforce discipline.

Hope is not inherently negative. In fact, it drives entrepreneurship, investment, and ambition within the Greek American community. The challenge arises when hope is disconnected from structure.

Online gambling platforms, promotional credits, slot tournaments, and live betting environments are part of modern digital entertainment. They are not shortcuts to guaranteed income. They are structured ecosystems built around probability and engagement.

When players approach bonuses analytically, review terms carefully, and maintain strict budgeting, the illusion fades. What remains is informed participation.

The economy of hope does not disappear. It evolves. Instead of promising effortless wealth, it becomes an invitation to engage responsibly, compare wisely, and treat digital wagering as entertainment supported by clear financial boundaries.

CLICK HERE TO DONATE IN SUPPORT OF DCREPORT’S NONPROFIT NEWSROOM

The post Illusion of Easy Money and the Economy of Hope appeared first on DCReport.org.

I kind of want to write about AI every day these days, but I’ve got to pace myself so you all don’t get overloaded. So here’s a roundup post with only one entry about AI. Just one, I promise!

Well, OK, there’s also a podcast episode about AI. I went on the truly excellent Justified Posteriors podcast to talk about the economics of AI with Andrey Fradkin and Seth Benzell. It was truly a joy to do a podcast with people who know economics at a deep level!

Anyway, on to this week’s roundup.

Erik Brynjolfsson believes that AI caused a productivity boom last year:

Data released this week offers a striking corrective to the narrative that AI has yet to have an impact on the US economy as a whole…[N]ew figures reveal that total payroll growth [in 2025] was revised downward by approximately 403,000 jobs. Crucially, this downward revision occurred while real GDP remained robust, including a 3.7 per cent growth rate in the fourth quarter. This decoupling — maintaining high output with significantly lower labour input — is the hallmark of productivity growth…My own updated analysis suggests a US productivity increase of roughly 2.7 per cent for 2025. This is a near doubling from the sluggish 1.4 per cent annual average that characterised the past decade…

Micro-level evidence further supports this structural shift. In our work on the employment effects of AI last year, Bharat Chandar, Ruyu Chen and I identified a cooling in entry-level hiring within AI-exposed sectors, where recruitment for junior roles declined by roughly 16 per cent while those who used AI to augment skills saw growing employment. This suggests companies are beginning to use AI for some codified, entry-level tasks.

But Martha Gimbel says not so fast:

There are three reasons why what we are seeing may not actually be a real jump in productivity—or an irreconcilable gap between economic growth and job growth…

First, productivity is noisy data…We shouldn’t overreact to one or even two quarters of data. Looking over several quarters, we can see that productivity growth has averaged about 2.2%. That is strong, but not unusually so…

Second…for GDP growth in 2025, we’re still waiting for [revisions to come in]. Note that any comparison of jobs data and GDP data for 2025 is comparing revised jobs data to unrevised and incomplete GDP data…

Third…GDP data has been weird in 2025 partly because of policy and behavioral swings around trade. If you look at job growth relative to private-domestic final purchases…[job growth] is still low, but not as low as it is relative to the GDP data…

[E]ven if you trust the productivity data…there are other explanations besides AI…One reason job growth in 2025 was so low was because of changes in immigration policy. If the people being removed from the labor force were lower productivity workers, that will show up as an increase in productivity even though the productivity of the workers who remain behind has not changed…

Second, if you look at the productivity data, it appears that much of the boost is coming from capital utilization due to increased productive investment…[A]t this point it is people investing in AI not people becoming more productive by using AI.

Meanwhile, in January, Alex Imas had a very good post about AI and productivity:

Alex gathers a bunch of studies showing that AI improves productivity in most tasks. But in the real world, productivity improvements from new technology famously come with a lag, as companies retool their business models around the new tech. For a while, productivity actually falls, then starts to rise once the new business models start working. This is called the productivity J-curve. Brynjolfsson thinks we’ve hit the rising part of the J-curve, but Alex thinks we haven’t:

At the macro level, these [micro] gains [from AI] have not yet convincingly shown up in aggregate productivity statistics. While some studies show a slow down in hiring for AI-exposed jobs—which suggests that individual workers are either becoming more productive or tasks are being automated—the extent and timing of these dynamics are currently being debated. Other studies have found no changes in hours worked or wages earned based on AI use.

Also, Brynjolfsson thinks that job loss in AI-exposed occupations is a sign of growing productivity. But that may not be the case; new technologies can grow productivity while increasing hiring, by creating new tasks for humans to do. A new survey by Yotzov et al. finds that although corporate executives in the U.S., Australia, and Germany expect AI to cut employment, employees themselves expect it to provide new job opportunities:

We survey almost 6000 CFOs, CEOs and executives from stratified firm samples across the US, UK, Germany and Australia…[A]round 70% of firms actively use AI…[F]irms report little impact of AI over the last 3 years, with over 80% of firms reporting no impact on either employment or productivity…[F]irms predict sizable impacts over the next 3 years, forecasting AI will boost productivity by 1.4%, increase output by 0.8% and cut employment by 0.7%. We also survey individual employees who predict a 0.5% increase in employment in the next 3 years as a result of AI. This contrast implies a sizable gap in expectations, with senior executives predicting reductions in employment from AI and employees predicting net job creation.

And a new study by Aldasoro et al. finds that in Europe, AI adoption seems to be increasing employment at the companies that adopt it:

Our results reveal three key findings. First, AI adoption causally increases labour productivity levels by 4% on average in the EU. This effect is statistically robust and economically meaningful…[T]he 4% gain suggests that AI acts in the short term as a complementary input that enhances efficiency…

Second, and crucially, we find no evidence that AI reduces employment in the short run. While naïve comparisons suggest AI-adopting firms employ more workers, this relationship disappears once we account for selection effects through our instrumental variable approach. The absence of negative employment effects, combined with significant productivity gains, points to a specific mechanism: capital deepening. AI augments worker output – enabling employees to complete tasks faster and make better decisions – without displacing labour. [emphasis mine]

Everyone seems to just assume that AI is a human-remover, and in some cases it is. But overall, it might actually turn out to be complementary to humans, like previous waves of technology; we just don’t know yet. The lesson here is that we don’t really know how technology affects productivity, growth, employment, etc. until we try it and see. The economy is a complex machine that reallocates a lot of stuff in very surprising ways.

So stay tuned…

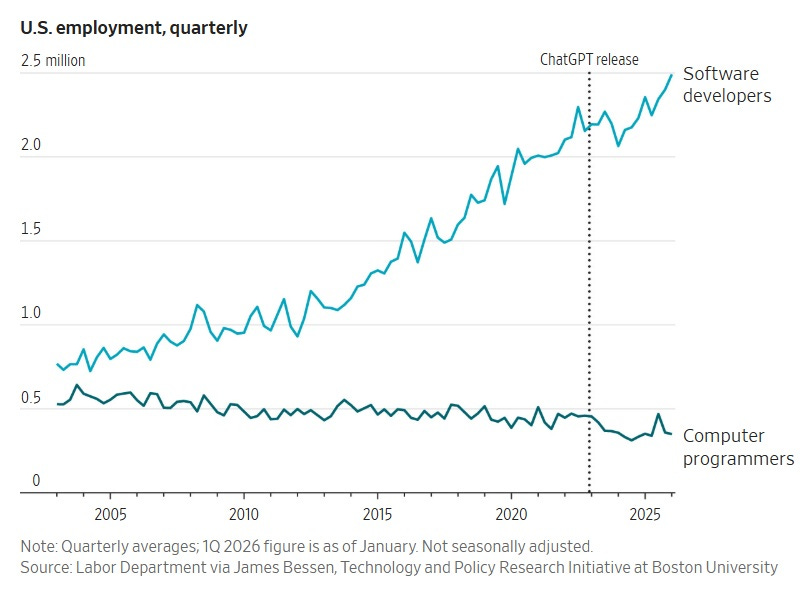

Update: Here is a good chart from the excellent Greg Ip of the Wall Street Journal:

Also, for what it’s worth, here’s Goldman Sachs:

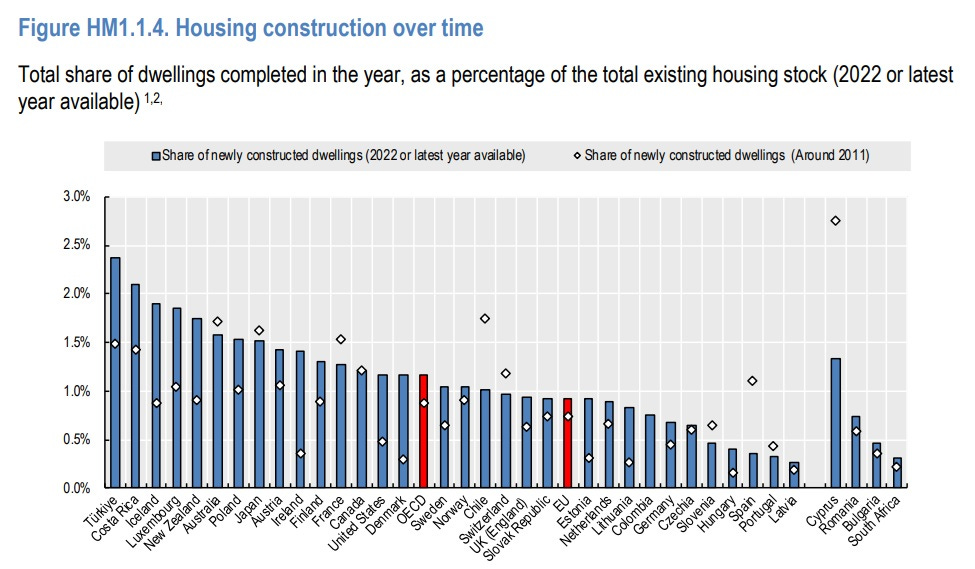

One of the most fun posts I’ve ever written was about how building high-end housing can reduce rents for lower-income people. I called it “Yuppie Fishtank Theory”:

The basic idea is very simple: If you build nice shiny new places for high earners (“yuppies”), they won’t go try to take over the existing lower-cost housing stock and muscle out the working class.

This is important because a lot of people believe the exact opposite. They think that if you build new market-rate (“luxury”) housing in an area, it’ll attract rich people, cause gentrification, and raise rents.

Over the years, my theory has been proven right — and the “gentrification” theory has been proven wrong — again and again. Here was a roundup I did of the evidence back in 2024:

Now Henry Grabar flags some new evidence that says — surprise, surprise — that Yuppie Fishtank Theory is still true:

A new study lays out exactly how a brand-new building can open up more housing in other, lower-income areas, creating the conditions that enable prices to fall…

In the paper, three researchers looked in extraordinary detail at the effects of a new 43-story condo project in Honolulu…What the researchers found was that the new housing freed up older, cheaper apartments, which, in turn, became occupied by people leaving behind still-cheaper homes elsewhere in the city, and so on…The paper estimates the tower’s 512 units created at least 557 vacancies across the city—with some units…creating as many as four vacancies around town…

To figure this out, the researchers…traced buyers arriving at the new apartments back to their previous homes and then, in some cases, they traced the new occupants of those homes back to prior addresses. The study found that the Central’s new residents left behind houses and apartments that were, on average, 38 percent cheaper, per square foot, than the apartments they moved into.

Yuppie Fishtanks win again!

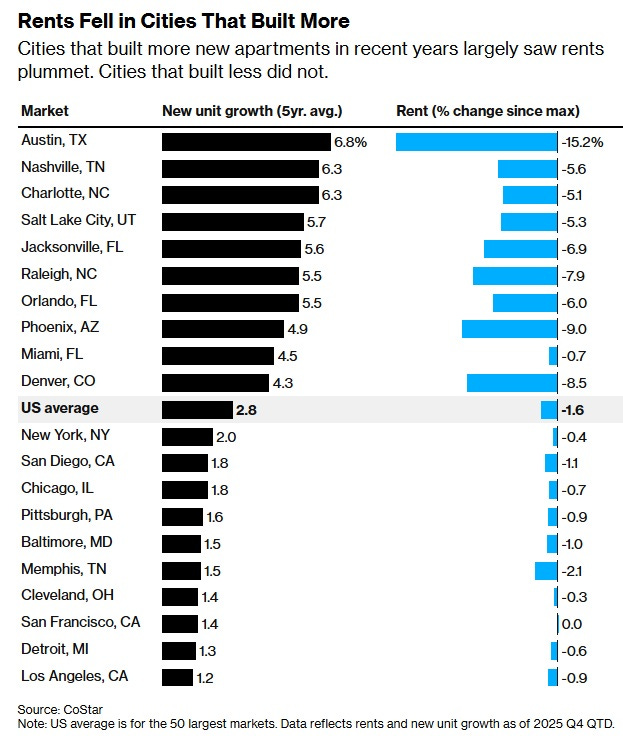

Cities that are applying Yuppie Fishtank Theory are seeing their rents fall. Here’s a Bloomberg story from December:

Rents got cheaper in several major cities this past year, thanks to an influx of luxury apartment buildings opening their doors and luring tenants to vacate their old homes…New building openings are bringing rents down as wealthy tenants trade up, forcing landlords to drop prices for older apartments. Rents for older units have fallen as much as 11%, and some are now on offer at rates as low as homes that are usually designated as “affordable”…The changed dynamic in the rental market is challenging the idea that luxury housing doesn’t help the broader ecosystem.

Overall, cities that build more housing are seeing lower rents:

At this point, “building housing reduces rent” is as close to a scientific law of the housing market as we’re likely to find.

Build more housing!!

Three years ago, David Oks and Henry Williams wrote a long post claiming that economic development was dead — that poor countries had done great in the post-WW2 decades when they sold raw materials to fast-growing rich countries, but that their growth in the 90s, 00s, and 10s was a bust. That was nonsense, and I wrote a lengthy rebuttal here:

Instead of rehashing that debate, I just want to link to Oks’ latest post, in which he expresses extreme pessimism about global poverty:

He cites a recent post by Max Roser of Our World in Data (the excellent site where I get many of the charts for this blog). Roser notes that extreme poverty — defined as the fraction of people living on less than $3 a day — has declined so much in South Asia, East Asia, and Latin America that it has basically vanished. This leaves Africa as the only region with an appreciable number of extremely poor people left (except for some parts of Central Asia). And since African poverty rates are not declining, and African population is growing much faster than population elsewhere, this means that the number of extremely poor people in the world is set to start rising again:

The first thing to note is that by using this chart, and by making this argument, David Oks directly contradicts his thesis from his 2023 article. In 2023, Oks argued that global development since 1990 had been disappointing; in his new post, Oks argues that poverty reduction in 1990-2024 everywhere outside of Africa was so incredibly successful that it basically went to completion and has nowhere left to go!

Oks’ old post was pessimistic about the entire developing world — South Asia, Latin America, Africa, and so on. In this new post, he retreats to pessimism about Africa alone. This is a significant retreat — it’s an implicit acknowledgement that development was very very real for the billions of poor people who lived outside Africa in 1990.

As for whether Oks is right about Africa, only time will tell. But note that the rising global poverty in the chart above is entirely a forecast. If African growth surprises on the upside — say, from solar power and AI — and African fertility falls faster than expected, then we could see Africa follow in the footsteps of the other regions.

Our goal should be to keep the pessimists embarrassed.

On paper, the U.S. is a lot richer than most other rich countries — including Canada:

In terms of per capita GDP, Canada is poorer than Alabama, America’s poorest state. Canada is a little less unequal than America, so the difference in median incomes between the two countries is smaller — only about 18% higher as of 2021 (though the gap is growing). But that’s still a sizeable gap!

Europeans, Australians, and Canadians who visit America’s disorderly and crime-ridden city centers can sometimes balk at this fact. They instinctively start groping for some reason the numbers must be wrong. But reporters from Canada’s Globe and Mail traveled to Alabama, and discovered that the numbers don’t lie — America really is just a very, very rich place, even compared to other countries. Here are some excerpts from their article:

For eons, Canadians have viewed Alabama as a small state that, save for a few pockets, is dirt poor…For an ego check, The Globe and Mail travelled to the Deep South to understand how this happened. Immediately, it was obvious Alabama is misunderstood. In Huntsville, there are as many Subaru Outbacks as there are pickup trucks, and the geography in Alabama’s two largest metropolitan areas – Birmingham and Huntsville – looks nothing like the historical imagery…

Alabama is also home to five million people…and its economy is booming. The state’s unemployment rate is now just 2.7 per cent, versus 6.5 per cent in Canada, and its major employers include Airbus SE and giant defence contractor Northrop Grumman Corp. The state has also morphed into an auto manufacturing powerhouse with plants from Mercedes-Benz AG, Toyota Motor Corp., Hyundai Motor Co. and more. In 2024, Alabama made nearly as many vehicles as Ontario…

As for Birmingham itself, there’s the beauty of the rolling hills, which deliver stunning fall foliage. And the city’s becoming a foodie hub. A new restaurant, Bayonet, was named one of America’s 50 best restaurants by The New York Times last fall. And despite the bible thumping, Birmingham has a sizable LGBTQ+ community and scored the same as Boston on the Human Rights Campaign’s Municipal Equality Index.

The Globe and Mail article notes that Alabama has a higher poverty rate and lower life expectancy than Canada — and being a newspaper in a progressive country, it fails to mention the much higher crime rate. But the fact is, for most Alabamans, the material standard of living is more comfortable than what prevails in much of Canada.

People who believe America’s wealth is fake need to go there and see for themselves that it’s real.

In general, economists find that immigration’s economic effect on the native born is either positive or zero. But one famous economist, George Borjas, consistently finds negative effects. This makes Borjas beloved of the Trump administration and the nativist movement in general — it’s very common to hear MAGA people cite Borjas in debates.

It’s very odd that one economist keeps getting results about immigration that are so out of whack with what everyone else finds. Well, it turns out that if you look closely at George Borjas’ methodologies, you find a lot of dodgy stuff. I wrote about this several times back during the first Trump administration, when I worked for Bloomberg. Here’s what I wrote in 2015:

[I]n 2015, George Borjas…came out with a shocking claim -- the celebrated [David] Card result [about the Mariel Boatlift not harming American workers], he declared, was completely wrong. Borjas chose a different set of comparison [cities]…He also focused on a very specific subset of low-skilled Miami workers. Unlike Card, Borjas found that the Mariel boatlift immigration surge had a big negative effect on native wages for this vulnerable subgroup.

Now, in relatively short order, Borjas’ startling claim has been effectively debunked. Giovanni Peri and Vasil Yasenov, in a new National Bureau of Economic Research working paper…find that Borjas only got the result that he did by choosing a very narrow, specific set of Miami workers. Borjas ignores young workers and non-Cuban Hispanics -- two groups of workers who should have been among the most affected by competition from the Mariel immigrants. When these workers are added back in, the negative impact that Borjas finds disappears.

But it gets worse. Borjas was so careful in choosing his arbitrary comparison group that his sample of Miami workers was extremely tiny -- only 17 to 25 workers in total. That is way too small of a sample size to draw reliable conclusions. Peri and Yasenov find that when the sample is expanded from this tiny group, the supposed negative effect of immigration vanishes.

All of this leaves Borjas’ result looking very fishy.

And here was a follow-up in 2017:

Recently, Michael Clemens of the Center for Global Development and Jennifer Hunt of Rutgers University found an even bigger problem with Borjas’ study. Clemens and Hunt noted that in 1980, the same year as the Mariel boatlift, the U.S. Census Bureau changed its methods for counting black men with low levels of education. The workers that Borjas finds were hurt by the Mariel immigration include these black men. But because these workers generally have lower wages than those the Census had counted before, Borjas’ finding of a wage drop among this group, the authors claim, was almost certainly a result of the change in measurement.

And here’s what I wrote in 2016:

Borjas has written a book…called “Immigration Economics.”…However, University of California-Berkeley professor David Card and University of California-Davis’ Peri have written a paper critiquing the methods in Borjas’ book. It turns out that the way Borjas and the economists he cites do immigration economics is very, very different from the way other researchers do it.

One big difference is how economists measure the number of immigrants coming into a particular labor market…[I]nstead of using the change in the number of immigrants, Borjas just uses the number of immigrants itself…This creates a number of problems.

Let’s think about a simple example. Suppose there are 90 native-born landscapers in the city of Cleveland, and 10 immigrant landscapers. Suppose that demand for landscapers goes up, because people in Cleveland start buying houses with bigger lawns. That pushes up the wages of landscapers, which will draws 100 more native-born Clevelanders into the landscaping business. But the supply of immigrants is relatively fixed. So the percent of immigrants in the Cleveland landscaping business has gone down, from 10 percent to only 5 percent, even though the number of immigrants in the business has stayed the same.

Borjas will find that the percent of immigrants in the business goes down just as wages go up. But to conclude that native workers’ wages went up because immigration went down would be totally incorrect, because immigration didn’t actually fall! In fact, Borjas’ method is vulnerable to reaching exactly this sort of erroneous conclusion. Card and Peri point out that if you use the more sensible measure, there’s not much correlation between immigrant inflows and native-born workers’ wages and income mobility.

In other words, there’s a clear pattern of Borjas using strange and seemingly inferior methods, and arriving at conclusions that diverge radically from his peers. So I was not exactly surprised when Jiaxin He and Adam Ozimek looked at Borjas’ recent work on H-1B workers also contained some very dodgy methodology:

Borjas’s February 2026 working paper attempted to answer whether H-1B workers earn less than comparable native-born workers by combining data on actual H-1B earnings with American Community Survey data on native workers. The conclusions are negative, with H-1B holders earning 16 percent less. But these findings result from substantial data errors.

…The most significant mistake is a crucial temporal mismatch between his H-1B and native-born samples: the H-1B applications span 2020-2023, while the ACS data covers just 2023.

Nowhere did the paper mention controlling for inflation or wage growth. Given 15.1 percent inflation and an 18.7 percent wage increase for software occupations alone from 2020 to 2023, comparing wages of H-1B workers from 2020 to 2023 to… native-born wages from 2023 only produces negatively biased results that overstates the wage gap…A simple approach is to directly compare the 2023 H-1B observations (FY 2024) to 2023 ACS data. Alternatively, we can use all years but adjust for inflation and convert all years to real 2023 dollars. Both approaches cut the wage gap roughly in half…

The second error stems from controlling for geographic wage drivers using each worker’s PUMA (public use microdata area)…The problem is that Dr. Borjas uses the PUMA where visa holders work alongside the PUMA where native workers live. Consider a native-born software developer working at Google in Mountain View who resides in a cheaper area like Fremont. If residential areas have lower average wages than business districts, this mismatch systematically inflates the apparent native wage and negatively biases the H-1B wage gap.

Another Borjas paper with serious methodological errors, and an anti-immigration conclusion that disappears when you correct the errors? Shocking!

By this point, it should be clear that whether these mistakes are intentional or not, Borjas’ anti-immigration conclusions tend to vanish when the mistakes are corrected. Borjas is not a good source of information on immigration topics; every time someone cites him in a debate, you know they haven’t looked seriously at the literature.

A big tech headline this week is Anthropic (makers of Claude, widely regarded as one of the best LLM platforms) resisting Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth’s calls to modify their platform in order to enable it to support his commission of war crimes. As has become clear this week, Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei has declined to do so. The administration couches the request as an attempt to use the technology for “lawful purposes”, but given that they’ve also described their recent crimes as legal, this is obviously not a description that can be trusted.

Many people have, understandably, rushed to praise Dario and Anthropic’s leadership for this decision. I’m not so sure we should be handing out a cookie just because someone is saying they’re not going to let their tech be used to cause extrajudicial deaths.

To be clear: I am glad that Dario, and presumably the entire Anthropic board of directors, have made this choice. However, I don’t think we need to be overly effusive in our praise. The bar cannot be set so impossibly low that we celebrate merely refusing to directly, intentionally enable war crimes like the repeated bombing of unknown targets in international waters, in direct violation of both U.S. and international law. This is, in fact, basic common sense, and it’s shocking and inexcusable that any other technology platform would enable a sitting official of any government to knowingly commit such crimes.

We have to hold the line on normalizing this stuff, and remind people where reality still lives. This means we can recognize it as a positive move when companies do the reasonable thing, but also know that this is what we should expect. It’s also good to note that companies may have many reasons that they don’t want to sell to the Pentagon in addition to the obvious moral qualms about enabling an unqualified TV host who’s drunkenly stumbling his way through playacting as Secretary of Defense (which they insist on dressing up as the “Department of War” — another lie).

Being on any federal procurement schedule as a technology vendor is a tedious nightmare. There’s endless paperwork and process, all falling squarely into the types of procedures that a fast-moving technology startup is likely to be particularly bad at completing, with very few staff members having had prior familiarity handling such challenges. Right now, Anthropic handles most of the worst parts of these issues through partners like Amazon and Palantir. Addressing more of these unique and tedious needs for a demanding customer like the Pentagon themselves would almost certainly require blowing up the product roadmap or hiring focus within Anthropic for months or more, potentially delaying the release of cool and interesting features in service of boring (or just plain evil) capabilities that would be of little interest to 99.9% of normal users. Worse, if they have to build these features, it could exhaust or antagonize a significant percentage of the very expensive, very finicky employees of the company.

This is a key part of the calculus for Anthropic. A big part of their entire brand within the tech industry, and a huge part of why they’re appreciated by coders (in addition to the capabilities of their technology), is that they’re the “we don’t totally suck” LLM company. Think of them as “woke-light”. Within tech, as there have been massive waves of rolling layoffs over the last few years, people have felt terrified and unsettled about their future job prospects, even at the biggest tech companies. The only opportunities that feel relatively stable are on big AI teams, and most people of conscience don’t want to work for the ones that threaten kids’ lives or well-being. That leaves Anthropic alone amongst the big names, other than maybe Google. And Google has laid off people at least 17 times in the last three years alone.

So, if you’re Dario, and you want to keep your employees happy, and maintain your brand as the AI company that doesn’t suck, and you don’t want to blow up your roadmap, and you don’t want to have to hire a bunch of pricey procurement consultants, and you can stay focused on your core enterprise market, and you can take the right moral stand? It’s a pretty straightforward decision. It’s almost, I would suggest, an easy decision.

We’ve only allowed ourselves to lower the bar this far because so many of the most powerful voices in Silicon Valley have so completely embraced the authoritarian administration currently in power in the United States. Facebook’s role in enabling the Rohingya genocide truly served as a tipping point in the contemporary normalization of major tech companies enabling crimes against humanity that would have been unthinkable just a few years prior; we can’t picture a world where MySpace helped accelerate the Darfur genocide, because the Silicon Valley tech companies we know about today didn’t yet aspire to that level of political and social control. But there are deeper precedents: IBM provided technology that helped enable the horrors of the holocaust in Germany in the 1940s, and that served as the template for their work implementing apartheid in South Africa in the 1970s. IBM actually bid for the contract to build these products for the South African government. And the systems IBM built were still in place when Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, David Sacks and a number of other Silicon Valley tycoons all lived there during their formative years. Later, as they became the vaunted “PayPal Mafia”, today’s generation of Silicon Valley product managers were taught to look up to them, so it’s no surprise that their acolytes have helped create companies that enable mass persecution and surveillance. But it’s also why one of the first big displays of worker power in tech was when many across the industry stood up against contracts with ICE. That moment was also one of the catalyzing events that drove the tech tycoons into their group chats where they collectively decided that they needed to bring their workers to heel.

And they’ve escalated since then. Now, the richest man in the world, who is CEO of a few of the biggest tech companies, including one of the most influential social networks — and a major defense vendor to the United States government — has been openly inciting civil war for years on the basis of his racist conspiracy theories. The other tech tycoons, who look to him as a role model, think they’re being reasonable by comparison in the fact that they’re only enabling mass violence indirectly. That’s shifted the public conversation into such an extreme direction that we think it’s a debate as to whether or not companies should be party to crimes against humanity, or whether they should automate war crimes. No, they shouldn’t. This isn’t hard.

We don’t have to set the bar this low. We have to remind each other that this isn’t normal for the world, and doesn’t have to be normal for tech. We have to keep repeating the truth about where things stand, because too many people have taken this twisted narrative and accepted it as being real. The majority of tech’s biggest leaders are acting and speaking far beyond the boundaries of decency or basic humanity, and it’s time to stop coddling their behavior or acting as if it’s tolerable. In the meantime, yes, we can note when one has the temerity to finally, finally do the right thing. And then? Let’s get back to work.

Up and to my office, whither several persons came to me about office business. About 11 o’clock, Commissioner Pett and I walked to Chyrurgeon’s Hall (we being all invited thither, and promised to dine there); where we were led into the Theatre; and by and by comes the reader, Dr. Tearne, with the Master and Company, in a very handsome manner: and all being settled, he begun his lecture, this being the second upon the kidneys, ureters, &c., which was very fine; and his discourse being ended, we walked into the Hall, and there being great store of company, we had a fine dinner and good learned company, many Doctors of Phisique, and we used with extraordinary great respect.

Among other observables we drank the King’s health out of a gilt cup given by King Henry VIII. to this Company, with bells hanging at it, which every man is to ring by shaking after he hath drunk up the whole cup. There is also a very excellent piece of the King, done by Holbein, stands up in the Hall, with the officers of the Company kneeling to him to receive their Charter.

After dinner Dr. Scarborough took some of his friends, and I went along with them, to see the body alone, which we did, which was a lusty fellow, a seaman, that was hanged for a robbery. I did touch the dead body with my bare hand: it felt cold, but methought it was a very unpleasant sight.

It seems one Dillon, of a great family, was, after much endeavours to have saved him, hanged with a silken halter this Sessions (of his own preparing), not for honour only, but it seems, it being soft and sleek, it do slip close and kills, that is, strangles presently: whereas, a stiff one do not come so close together, and so the party may live the longer before killed. But all the Doctors at table conclude, that there is no pain at all in hanging, for that it do stop the circulation of the blood; and so stops all sense and motion in an instant.

Thence we went into a private room, where I perceive they prepare the bodies, and there were the kidneys, ureters [&c.], upon which he read to-day, and Dr. Scarborough upon my desire and the company’s did show very clearly the manner of the disease of the stone and the cutting and all other questions that I could think of … [Poor Mr. Wheatley could not even stand a medical lecture on physiology. D.W.] [and the manner of the seed, how it comes into the yard, and – L&M] how the water [comes] into the bladder through the three skins or coats just as poor Dr. Jolly has heretofore told me.

Thence with great satisfaction to me back to the Company, where I heard good discourse, and so to the afternoon Lecture upon the heart and lungs, &c., and that being done we broke up, took leave, and back to the office, we two, Sir W. Batten, who dined here also, being gone before.

Here late, and to Sir W. Batten’s to speak upon some business, where I found Sir J. Minnes pretty well fuddled I thought: he took me aside to tell me how being at my Lord Chancellor’s to-day, my Lord told him that there was a Great Seal passing for Sir W. Pen, through the impossibility of the Comptroller’s duty to be performed by one man; to be as it were joynt-comptroller with him, at which he is stark mad; and swears he will give up his place, and do rail at Sir W. Pen the cruellest; he I made shift to encourage as much as I could, but it pleased me heartily to hear him rail against him, so that I do see thoroughly that they are not like to be great friends, for he cries out against him for his house and yard and God knows what. For my part, I do hope, when all is done, that my following my business will keep me secure against all their envys. But to see how the old man do strut, and swear that he understands all his duty as easily as crack a nut, and easier, he told my Lord Chancellor, for his teeth are gone; and that he understands it as well as any man in England; and that he will never leave to record that he should be said to be unable to do his duty alone; though, God knows, he cannot do it more than a child. All this I am glad to see fall out between them and myself safe, and yet I hope the King’s service well done for all this, for I would not that should be hindered by any of our private differences.

So to my office, and then home to supper and to bed.

Links for you. Science:

Archaeologists are lifting 70- to 80-ton stones from the legendary Lighthouse of Alexandria, and the most intriguing part is that some pieces appear to be part of a long-lost monumental doorway

Long Covid could trigger changes in the brain that are similar to Alzheimer’s, new study says

Plasmids weaponize conjugation to eliminate non-permissive recipients

COVID-19 vaccine trust and uptake: the role of media, interpersonal and institutional trust in a large population-based survey

Avian flu behind mass skua die-off in Antarctica, scientists say

Dinosaur Convention Bans All Paleontologists Named in Epstein Files Out of ‘Safety of Our Attendees’

Other:

Zionism was never a single concept. We should be grateful to JFNA’s survey for the reminder.

Illinois Is In Danger of Electing a MAGA-Aligned Dem to the Senate (his major opponent, Stratton, opposes the filibuster, so she passes that basic test)

Mamdani Chose Her to Manage City Housing. Then She Had to Find an NYC Rental.

The real reason Hakeem Jeffries cussed out Donald Trump

Worker in the governor’s office could be about to lose her job because the regime won’t renew her work visa

Homeland Security Hires Labor Dept. Aide Whose Posts Raised Alarms

Border Patrol Cmdr. Gregory Bovino praised agent after shooting Marimar Martínez in Chicago, evidence shows

The FBI seizure of Georgia 2020 election ballots relies on debunked claims

How a 150-year-old Japanese workshop survived the age of slop and distraction

‘The Trust Has Been Absolutely Destroyed’: Some state election officials say they no longer trust their federal partners.

The Trump Bubble Is Impregnable for Now—but Boy, Is It Going to Burst

Abolition, Amnesty, Decriminalization, Open Borders: You may not believe immigration restrictions are racist, but racists believe immigration restrictions are racist.

We Have to Look Right in the Face of What We Have Become

Dave Jorgenson Is Now Generating 2.5x More YouTube Views Than The Washington Post

Airspace closure followed spat over drone-related tests and party balloon shoot-down, sources say

The GOP’s “Show Us Your Papers” Bill Is the Latest Effort to Help Trump Take Over Elections

WHEN TRUMP LEAVES OFFICE, YOU’LL BARELY NOTICE THE DIFFERENCE IN THE GOP

Watching the watchers: ICE uses facial recognition to track citizen observers in Minnesota, federal court filing says

ICE Moved Detainees to Previously Undisclosed Floor of 26 Federal Plaza

High-speed car chase involving federal agent ended with multi-car crash at Nina’s in St. Paul

CBP Signs Clearview AI Deal to Use Face Recognition for ‘Tactical Targeting’ (I have no idea why CBP needs to ““disrupt, degrade, and dismantle” people and networks viewed as security threats.”)

Pam Bondi has fully drunk the Kool-Aid. Her latest hearing about the Epstein files proves it

What Peter Thiel Saw in Jeffrey Epstein

Government Loses Hard Drives It Was Supposed to Put ICE Detention Center Footage On

Donald Trump Is Really Racist: The president not only traffics in racist rhetoric, but also racist policies, and we should not shy away from pointing out the harms.