Dan Simmons, RIP

Alas, he has passed away. A great writer, you should start with Hyperion if you have not read it already.

The post Dan Simmons, RIP appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

Alas, he has passed away. A great writer, you should start with Hyperion if you have not read it already.

The post Dan Simmons, RIP appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

The liver is one of the most powerful organs in the body, but it’s one we also take for granted, particularly when it comes to alcohol. The liver filters toxins, supports our digestion and stores energy, as well as regulating many other processes in the body.

We all know that alcohol isn’t good for the liver and it’s fair to say we know that heavy drinking or regular alcohol consumption can cause lasting damage. But that will never happen to us, right? Liver damage only happens to those that end up in an alcohol dependence clinic and have a really heavy dependence on booze. Wrong.

Alcohol related liver damage can develop gradually and over time really have an impact on a person’s life, to the point of death in fact, so while it’s important to drink in moderation and live a healthy and balanced lifestyle, it’s also important to notice the early signs too.

Here are five signs that alcohol may be starting to affect your liver…

Feeling unusually tired or lacking energy can be one of the earliest signs that your liver is under pressure. When the liver is struggling to function efficiently, the body’s ability to process toxins and store energy becomes compromised. This can leave you feeling sluggish, weak, or unable to concentrate. Although fatigue has many possible causes, stress, poor sleep, low mood, or nutrition, it is worth paying attention to if it coincides with regular drinking or follows periods of heavier alcohol use.

The liver plays a vital role in digestion, especially in producing bile, which helps your body break down fats. When alcohol begins to affect liver function, you may notice changes in your appetite or digestion. These can include:

While these symptoms are common in various conditions, they can also be early indicators that your liver is struggling to cope with alcohol intake.

Discomfort in the upper right side of the abdomen, where your liver is located, may be a sign of inflammation. This discomfort can feel like a dull ache, pressure, or sensitivity in that area. Sometimes it appears after drinking, but it can also be present at other times. If the liver becomes enlarged or irritated from repeated alcohol exposure, this may create sensations of tightness or swelling. Any persistent abdominal pain should be assessed by a healthcare professional to rule out more serious issues.

One of the more noticeable signs of liver strain is jaundice, which causes the skin or the whites of the eyes to appear yellow. This happens when the liver is unable to process bilirubin, a waste product created when red blood cells break down. Jaundice is usually a sign of more significant liver impairment and should be taken seriously.

Other skin changes can also signal liver stress, including:

These symptoms can arise when the liver’s ability to regulate blood components is compromised.

Finally, because the liver plays a key role in processing waste products, changes in urine and stool colour can indicate something is amiss. Dark urine, even when hydrated, or pale, clay-coloured stools may suggest the liver is struggling to process bile effectively. While temporary changes can occur due to diet, medications, or short-term illness, persistent differences are worth discussing with a healthcare professional.

In fact, if any of the above feel familiar to you, it’s worth seeking help from your doctor and exploring your relationship with alcohol to enable your liver and overall wellbeing to recover.

Photo: lyashenko via their website.

CLICK HERE TO DONATE IN SUPPORT OF DCREPORT’S NONPROFIT NEWSROOM

The post Five Signs Alcohol Is Having an Impact on Your Liver appeared first on DCReport.org.

Peru’s Marxist President Changes His Mind, Doesn’t Make Hernando de Soto Prime Minister

Remember Gilda Radner?

The post “Never mind…” appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

That is from the new AER Insights by Jonathan Chiu and Cyril Monnet:

Central bankers argue that programmable digital currencies may compromise the uniformity or singleness of money. We explore this view in a stylized model where programmable money arises endogenously, and differently programmed monies have varying liquidity. Programmability provides private value by easing commitment frictions but imposes social costs under informational frictions. Preserving uniformity is not necessarily socially beneficial. Banning programmable money lowers welfare when informational frictions are mild but improves it when commitment frictions are low. These insights suggest that programmable money could be more beneficial on permissionless blockchains, where it is difficult to commit but trades are publicly observable.

Recommended.

The post On the Programmability and Uniformity of Digital Currencies appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

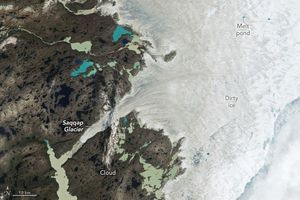

New NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman announced a major overhaul of the agency’s Artemis moon program Friday, acknowledging that the agency’s plan to land astronauts on the moon in 2028 was not realistic without another preparatory mission first to lay the groundwork.

He said NASA will now add an additional flight in 2027 in which astronauts will dock with new commercial moon landers in low-Earth orbit for detailed tests of navigation, communications, propulsion and life support systems, along with verifying rendezvous procedures.

That flight, in turn, will be followed by at least one and possibly two lunar landing missions in 2028 that incorporate lessons learned from the preceding flight.

The goal is to accelerate the pace of launches of the huge Space Launch System rocket while carrying out Artemis flights in evolutionary steps — not attempting missions that rely on too many untested technologies and procedures at once.

“We’re going to get there in steps, continue to take down risk as we learn more and we roll that information into subsequent designs,” Isaacman said told CBS News. “We’ve got to get back to basics.”

Isaacman outlined the plan in an interview with CBS News space contributor Christian Davenport and then again during a news conference Friday.

The announcement came two days after release of a sharply-worded report from NASA’s independent Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel that deemed the existing plans too risky.

The panel raised concerns about the number of “firsts” required by the original Artemis III moon landing mission and recommended that NASA “restructure” the program to create a more balanced risk posture.

“It is interesting that a lot of the things that we are addressing directly go to the points they raised in their report,” Isaacman said Friday. “I can’t say we actually collaborated on it because I generally think these were all pretty obvious observations.”

He said he told the panel “we are completely aligned, I agree with every one of the points that you raised.”

The revised Artemis architecture also comes as NASA has been struggling to launch the delayed Artemis II mission on a flight to send four astronauts on a trip around the moon.

Launch had been planned for early February, but it was delayed to repair a hydrogen leak and, more recently, to give engineers time to fix a helium pressurization problem in the rocket’s upper stage. Launch is now on hold until at least April 1.

The Artemis III mission, which had been expected to land astronauts near the moon’s south pole in 2028, now will be redefined and rescheduled — launching ahead of schedule in 2027 but not to the moon, Isaacman said.

Instead, yet-to-be-named astronauts will rendezvous and dock in orbit closer to home with one or both of the commercially built lunar landers now under development at Elon Musk’s SpaceX and Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin.

The idea is to gain valuable near-term flight experience before attempting a moon landing with astronauts on board. With Artemis III under its belt, NASA hopes to launch two moon landing missions in 2028, Artemis IV and V, using one or both landers, and to continue with one moonshot per year thereafter.

“What helps us get to the moon? Well, for sure, rendezvous and docking with one or ideally both landers, that gives you an opportunity to do some integrated testing of a vehicle that we are going to depend upon the following year to take those astronauts down to the surface of the moon,” Isaacman told CBS News.

The revised Artemis III mission will also give astronauts a chance to test out new , commercially provided spacesuits future moonwalkers will use on the lunar surface.

“It’s an opportunity to … actually have the suits in microgravity, even if we don’t go outside the vehicle in them. You get a lot of good learning from that,” Isaacman said.

The Artemis III test flight with one or two lander dockings in Earth orbit is similar in concept to Apollo 9, which launched a command module and lander to Earth orbit for flight tests in 1969 and helped pave the way to the Apollo 11 landing four months later.

Isaacman said SpaceX and Blue Origin are “both looking to do uncrewed landing demonstrations as part of the existing agreement.”

“So we want to just take advantage of this to set up both vendors for future success on a lunar landing,” he said. “This is the proper way to do it, if it works out from a timing perspective, to be able to rendezvous and dock with both. … This, again, is the right way to proceed in order to have a high confidence opportunity in ’28 to land.”

The Artemis IV and V missions in 2028 will use whichever landers are deemed ready for service. If only one company’s lander is available, that lander would be used for both missions, an official said. If both are available, one would be used for one flight and one for the other.

Launching Artemis III, IV and V before the end of 2028 will not be easy, and Isaacman said it is essential that NASA rebuild its workforce and regain the technical competence to support a higher launch cadence, moving from one flight every three years or so to a flight every year. That pace, he argued, will reduce risk.

“When you regain these core competencies and you start exercising your muscles, your skills do not atrophy,” he said. “It’s safer. And yes, you are buying down risk, because you’re able to test things in low Earth orbit before you need to get to the moon, which is exactly what we did during the Apollo era.”

He said he did not blame NASA’s contractors for the current slow pace of Artemis launches. Instead, “we should have made better decisions (in the past) and said, you don’t go from Artemis II to landing on the moon with Artemis III.”

Officials said Isaacman had discussed accelerating lander development with both SpaceX and Blue Origin and that both were on board. He also discussed the accelerated Artemis overhaul with Boeing, which manages the SLS rocket and builds its massive first stage; with United Launch Alliance, builder of the rocket’s upper stage, Orion-builder Lockheed Martin and other Artemis contractors.

All, the official said, were in agreement.

“Boeing is a proud partner to the Artemis mission and our team is honored to contribute to NASA’s vision for American space leadership,” Steve Parker, the president and CEO of Boeing Defense, Space & Security, said in a statement. “We are ready to meet the increased demand.”

Isaacman also said the agency would halt work to develop a more powerful version of the SLS rocket’s upper stage, known as the Exploration Upper Stage, or EUS. Instead, NASA will go forward with a “standardized,” less powerful stage but one that will minimize major changes between flights and utilize the same launch gantry.

Under the original Artemis architecture, NASA planned on multiple versions of the SLS rocket, ranging from the “Block 1” vehicle currently in use to a more powerful EUS-equipped Block 1B and eventually an even bigger Block 2 model using advanced solid rocket boosters. The latter two versions required use of a taller mobile launch gantry, already well under construction at the Kennedy Space Center.

“It is needlessly complicated to alter the configuration of the SLS and Orion stack to undertake subsequent Artemis missions,” Amit Kshatriya, NASA’s associate administrator, said in a statement.

“The entire sequence of Artemis flights needs to represent a step-by-step build-up of capability, with each step bringing us closer to our ability to perform the landing missions. Each step needs to be big enough to make progress, but not so big that we take unnecessary risk given previous learnings.”

As a result, NASA will stick with the current version of the SLS with the addition of the “standardized” upper stage. No other details were provided.

Isaacman closed out the CBS interview by saying flight-tested hardware, a revitalized work force and a more Apollo-like management strategy are only part of the story.

“There’s another ingredient that’s required, and that’s the orbital economy, whether it happens in low-Earth orbit or on the lunar surface,” Isaacman said.

“We’ve got to do something where we can get more value out of space and the lunar surface than we put into it. And that’s how you really ignite an economy, and that’s how everything we want to do in space is not perpetually dependent on taxpayers.”

2. Jimi Hendrix as systems engineer.

3. NYT on the possible Nevis charter city.

4. New teen mental health problems in Australia?

5. Jacinda Ardern is moving to Australia (NYT).

6. Chris Blattman on using Claude Code for social science.

7. “Young computer science graduates were employed at near record-high rates in 2024.“

The post Friday assorted links appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

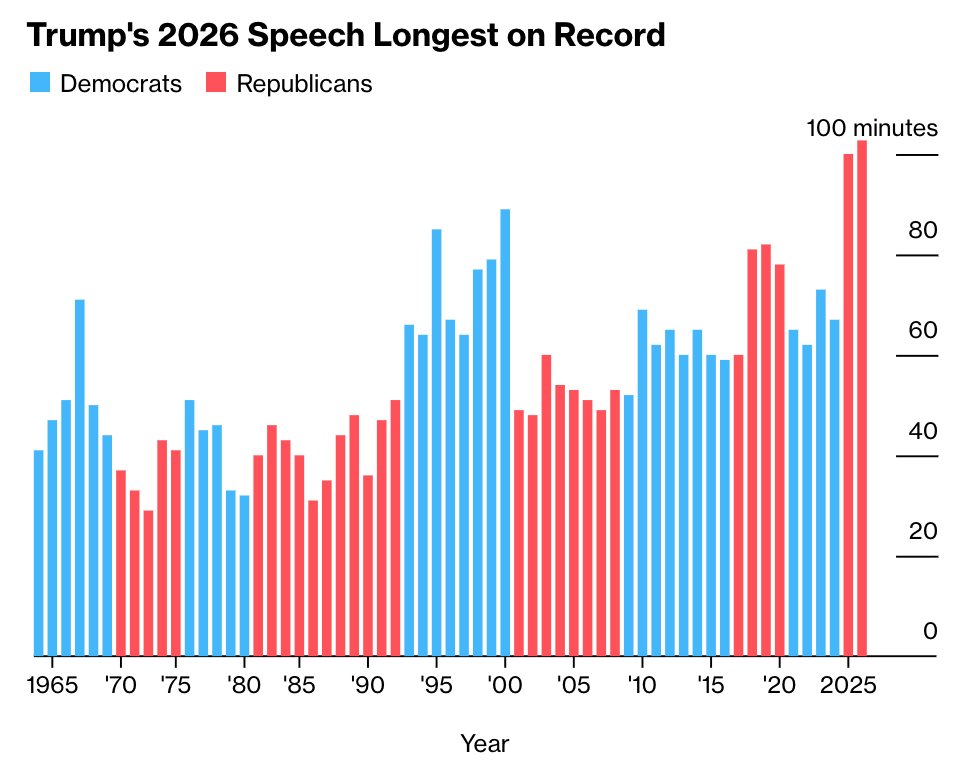

Kate and Josh discuss Trump’s extremely lengthy State of the Union, new information about an allegation against him in the Epstein files, and the dark scandal engulfing Rep. Tony Gonzales (R-TX).

Watch and subscribe to see all of our video content on our YouTube page.

You can listen to the new episode of The Josh Marshall Podcast here.

The Post has an article today, an exclusive they say, about a draft executive order purportedly being circulated between the White House and various conspiracy theorists and right-wing extremists in its broader circle. The proposed order claims that China has been found to be interfering in U.S. elections — specifically rigged the 2020 election in Joe Biden’s favor — and that as a result of that the president, as commander-in-chief, can and must directly take control of U.S. elections for the midterms and the 2028 presidential elections.

Two points merit saying on this. The first is that these are the rehashed, insane theories that were literally and figuratively laughed out of court in 2020. These are all absurd. Everybody knows they are absurd and false. The legal theory is what demands our attention. The authors of the order believe that if something is an emergency the president can invoke a kind of hidden dictator clause in the Constitution which allows him to assert powers which the Constitution explicitly forbids to him. This is not so. They secondarily believe in what we might call a “because” or “therefore” logic or clause. So because we have found that Threat X exists, the president can do whatever he wants to combat that threat. And as commander-in-chief, he can do anything he wants. This is also not so.

The Post, as is typical for most MSM publications, doesn’t quite know how to deal with a set of facts like this and treats it as a kind of mystery since such a non-existent power has never been claimed or litigated. So, for instance, down toward the bottom of the article we read this: “Article I, Section 4 of the Constitution assigns power to regulate elections to state legislatures and Congress, with no role for the president … A presidential emergency on elections has never been tested in court.” It’s true that this has never been tested in court. But lots of absurd things have never been tested in court.

Some people might get up in arms about this. And it’s definitely right to be up in arms in the sense of being vigilant or ready to fight over it. But this is a bogus theory and a bogus constitutional argument. I think there is little chance any judges will go for it. But more to the point, states, these subordinate but separate sovereignties, have their own standing to refuse unconstitutional invasions of their sovereign authority. Trump’s angle is always to keep others guessing about what he will do or what he’ll be allowed to do by this or that corrupted agency or court. Don’t do that. Every state should make clear proactively that an illegal military takeover of their state’s sovereign power to conduct its own elections will not be tolerated, accepted or submitted.

Period. End of story. The issue is not simply President Trump’s never-ending efforts to destroy the Republic, violate the Constitution, etc. Again, the Constitution is crystal clear about who runs and controls elections. States do that with guidelines set by Congress. Period. The issue is whether we — everyone, the opposition, everyone who purportedly needs to be in perpetual orbit around Donald Trump’s degenerate brain — need to always be allowing him the initiative. Does everyone have to be waiting and thinking how to respond to his actions? No. States are obligated to maintain their unchallenged and unchallengeable sovereign power to conduct elections, in line with laws passed by Congress. Nothing anyone says to the contrary matters. Not any executive order. Not any court. No one. Period. End of story.

I wanted to alert you of something we’re on today. Among other things, it’s the kind of off-the-beaten-path reporting your membership dollars pay for. We sent David Kurtz to Nashville today for a hearing in the Abrego Garcia case. Since we’re a number of ICE murders and false imprisonments down the line at this point, remember that the Justice Department conceded that Abrego Garcia had been erroneously included among those sent last spring to the bespoke dungeon facility in El Salvador. He was brought back to the U.S. only after he was hit with a new indictment. His lawyers have argued to the judge in the case that the charges should be dismissed because this is a case of vindictive prosecution. Normally this is an extremely high bar for the defense to clear. But in this case, the judge replied by saying that he’s inclined to think that the defense is right. Today’s hearing was scheduled to give the government the opportunity to prove that the defense and (mostly) the judge are wrong.

What makes us interested in this case is not simply Abrego Garcia’s fate. As we know, Trump is quite big on vindictive prosecutions at the moment. But the Comey and James indictments have been dismissed on what are essentially technical reasons. So this is the first chance in Trump II where we’re going to see this issue litigated. It’s a really important hearing. After the hearing David Kurtz and John Light are going to do a live discussion you can tune into to find out what we learned. Check back here soon for details on how you can join. (A text story will follow, of course, too.)

It’s a cliché and more or less true that the Constitution’s “high crimes and misdemeanors” language can mean whatever Congress wants it to mean. That is not only because in this area Congress’ decision-making is certainly un-reviewable. It is because the Constitution’s writers were intentionally expansive in their definition. They were most focused not on statutory crimes but misrule. I wanted to take a moment to note that what we have unfolding in Minnesota is really a definitional impeachable offense.

I say this with no expectation that he will be charged with it, let alone convicted and removed from office, certainly not under Republican rule. But these are precisely the kinds of abuses of power, unconstitutional actions, that are most squarely within the impeachment mechanism’s meaning.

President Trump first undertook what amounts to an invasion of the state, with poorly trained and abusive paramilitaries creating menace, mayhem and death. The aim of this action was to terrorize and dominate the state. It wasn’t about immigration enforcement. Now, having been forced to scale back at least the visibility of their invasion of the state, they are resorting to cutting off budgetary support for social services programs. This money is distributed pursuant to congressional law. The executive branch has no right to impound it based on some vague definition of not being a good “custodian” of the money.

I don’t expect to get much disagreement when I say these are illegitimate actions. I doubt even the administration expects this decision to withstand judicial scrutiny. These are abuses that go far beyond statutes or criminal law. The president is elected to see that the laws are carried out, ensure the national defense and prosperity and provide civilian leadership of the armed forces. He has no right to go to war with states or regions he disagrees with politically, or has a vendetta against, or to try to coerce or punish them into compliance.

The fact that Trump won’t be impeached for this, at least not this year, shouldn’t obscure the fact that he should be, that these are the basic forms of misrule that merit removal from office, that quite apart from the statutory legality of specific actions, the entire class of actions — coercion by violence and theft of funding — is ruled out entirely.

News came today that Warner Bros Discovery decided that Paramount-Skydance’s bid ($111 billion) to acquire the company was superior to that from Netflix ($82.7 billion). WBD told Netflix it had four days to up its offer. Little more than an hour later Netflix said it didn’t need four days. It was bowing out. The deal was no longer economic at the price Paramount was offering. An additional fact is that Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos was at the White House while these things were happening, apparently trying to see whether Netflix had the thing any major company needs for a merger in 2026: the personal approval of Donald Trump. Apparently they didn’t have it. That’s the autocracy playbook. And at the federal level, that’s the game we’re playing right now.

We’ve discussed this deal many times over the last year. As a site interested in the business of news and the future of democracy, we’ve been mostly focused on the fate of CNN, which is owned by WBD. Today’s events make it highly, highly likely that CNN will come under the control of the Ellison family, “eldest son” David specifically, who has already put Bari Weiss in charge of CBS News. This is an oligarch-owned effort to build a pro-Trump state media behemoth with the addition of money from the Gulf princes and other members of the global Team Autocracy.

It’s probably the end of CNN as we know it, though perhaps the denouement will take a while.

At the same time, if we set aside the anti-democracy parts of the deal, it doesn’t look like a great business deal. It’s basically a bet on the dying medium of cable. There’s more in WBD than that. But that’s a whole lot of it. And Paramount-Skydance is also paying quite a lot of money for it. I feel much more equipped to make a judgment about the democracy side of this than the business side. But my publishing and media knowledge, such as it is, makes me skeptical of the business logic. And to the extent markets are making a judgment, they seem to agree. We also need to bear in mind that the Ellisons have no real experience in the media space at all. And this is all being quarterbacked by Larry Ellison’s doofus son, David. It really looks like Succession, only dumber, with the idea that Donald Trump’s backing, which is golden for forcing mergers on Trump’s terms, will make the whole thing work in business terms. They seem to be making big bets on Trumpism being forever. So I wouldn’t assume they know things you or I don’t.

Of course, we can’t actually set the democracy parts of this aside. CNN being delivered into the maw of the Trumpist/MAGA beast is a very bad thing for independent media and news. Very bad.

To me it’s sad inasmuch as CNN was a true pioneer in digital news, in its heyday it was a kind of updated version of a global news service, as BBC had once been. But things change. Here’s a look at CNN brass trying to put the best face on things and not jump to conclusions. But there’s a good chance Bari Weiss, or someone working at her behest, will be running the place by the end of the year. And I would caution against thinking — as Trump and the Ellisons seem to — that you can simply Foxify CNN or other news organizations and have the same audience keep watching. We’re seeing what happens to CBS. Audience is leaving. It’s being run into the ground. Sad for the CBS News legacy. But that audience will go elsewhere.

We should have some confidence that billionaires’ and Gulf princes’ ability to simply buy up all the news organizations is not perhaps as rock solid a plan as people seem to think. Audience can move. In our current reality, there’s MAGA, which wants Fox and the various Trump/state news service channels, and there’s the anti-Trump opposition, which leans heavily on actual news sites and channels. I don’t think that will change. Audiences will migrate. So yes, this is a bad, bad development. A major reverse. But it’s far from the end of the story for free media in the United States. It’s part of the Late Trumpism corruption. That’s my take.

TPM’s David Kurtz has been covering, in person, a hearing in Nashville in which the Trump administration sought to prove it did not pursue a vindictive prosecution against Kilmar Abrego Garcia, the man it erroneously imprisoned in El Salvador last year. Immediately upon leaving the courtroom, David sat down with me to record a Substack Live on what happened. Watch that here:

You’ll recall that Abrego Garcia’s lawyers in 2025 fought his removal from the country and won, a decision the Supreme Court affirmed. The Trump administration returned him to the U.S. last summer — but only after he was indicted on new, criminal charges. His lawyers argued that those new charges were a vindictive prosecution, meant to punish him for successfully fighting his rendition to CECOT, and that the judge should throw out the case. Vindictive prosecution is usually a challenging claim to prove in court, but U.S. District Judge Waverly Crenshaw found Abrego Garcia’s argument credible, and ordered the Trump administration to prove the prosecution was not vindictive. That’s what today’s hearing was for.

2025 saw many prosecutions that were clearly intended as retribution against people who the Trump administration understood to be its enemies, but this is the first time a vindictive prosecution claim has reached the point of, potentially, getting a case dismissed. That broader context is a big part of why we’re covering it today.

Watch the video above to get David’s read out on what happened during today’s hearing.

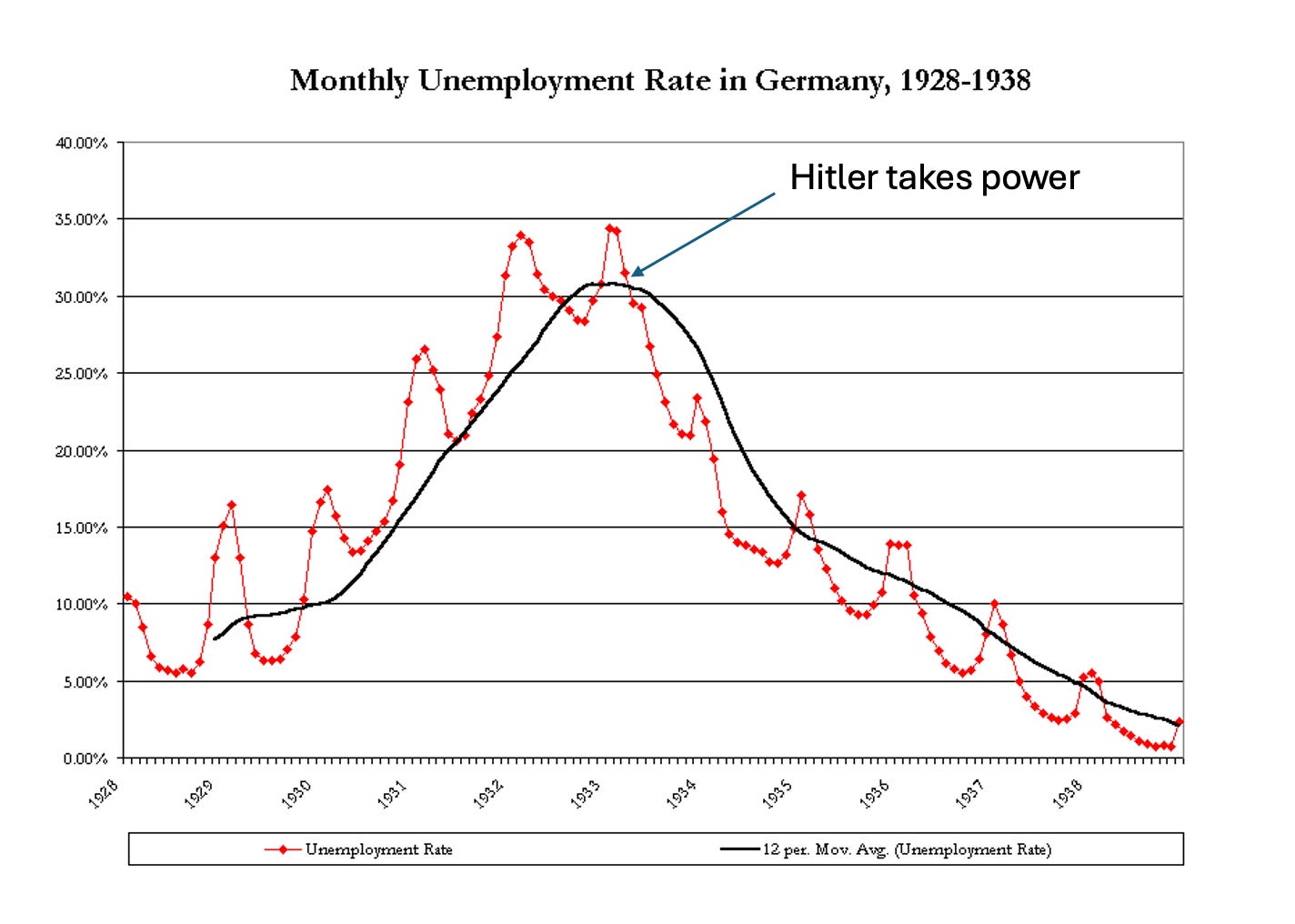

When Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, Germany’s economy was in dire straits. Under Chancellor Heinrich Brüningthe German government had clung dogmatically to economic orthodoxy in the face of the Great Depression, staying on the gold standard and imposing ever harsher fiscal austerity. The result was economic devastation and extremely high unemployment.

Hitler broke with the economic orthodoxy, enabling him to preside over a rapid economic recovery. The popularity he gained from the economic revival allowed him to consolidate power.

When Vladimir Putin came to power in 1999, Russia had just experienced a devastating financial crisis. The crisis precipitated a severe recession, forced the Russian government to default on its debt, and led to a plunge in the value of the ruble:

Source: FRED

Putin brought stability and presided over a strong economic recovery. And, as with Hitler, the upswell of popular support enabled Putin to consolidate power.

Donald Trump’s return to power in January 2025 was largely thanks to public dissatisfaction with the Biden economy. However, there was no economic crisis: unemployment was low and inflation had declined sharply from its peak in 2022. In 2024, the widely cited “misery index,” the sum of unemployment and inflation, was low by historical standards:

Source: FRED

And because there was no crisis when he regained the presidency, Trump — his bombastic lies in the State of the Union notwithstanding — hasn’t been able to preside over a clear economic improvement. Indeed, his approval on economic issues has plummeted:

Disclaimer: I am not saying that all was well with the Biden economy. I don’t want to revisit the vibecession debate at length today. Suffice it to say that, as Mike Konczal documents, there were reasons American families felt stressed despite good conventional numbers, although the depth of their discontent remains startling. But because America wasn’t suffering a Germany 1932 or Russia 1998-type crisis, it was impossible for Trump to deliver rapid economic improvement – that is, it would have been impossible even if he were competent (which he isn’t). So his efforts to consolidate power aren’t succeeding the way he and his fellow authoritarians expected.

On Wednesday the historian Tim Snyder, who is an expert on the grim history of Central and Eastern Europe, published a post titled Fascist Failure about the Trump administration’s lagging attempt to bring fascism to America. For now, I willbe more cautious and say that American fascism is faltering rather than failing. But the power grab is clearly not going according to plan. Why?

First and foremost, the determination and courage of ordinary Americans — in utter contrast with the craven surrender of much of the elite — has been crucial. But there are also structural factors that have helped the resistance.

Snyder emphasizes the lack of a good enemy against whom Trump can mobilize the nation. It’s a fair point. Trump spent more time in the SOTU bragging about his triumph in Venezuela than he spent talking about affordability, but the public was utterly unimpressed by his Maduro adventure. And there is no appetite at all for a confrontation with Iran.

Yet in my view that’s secondary to the fact that Trump can’t credibly claim to be an economic savior. Although I haven’t done a systematic study, I believe that most successful authoritarian takeovers occur in the aftermath of economic crises — crises that the newly installed dictator can claim to have solved. In an ideal world people wouldn’t accept tyranny just because the tyrant appears to deliver a higher standard of living. In the real world, however, they often do.

But that tactic is unavailable to Trump. While he can and does lie about the Biden economy, claiming that it was catastrophically bad, while touting the current economy as the greatest ever, people aren’t buying it. A plurality of Americans now say that Biden was a better president than Trump, and a majority say that the economy under Biden was better. Trump simply can’t gaslight Americans into disbelieving their lying eyes and wallets.

Could Trump possibly adopt policies that win broad public approval, thereby greasing the rails for his demolition of democracy? Maybe, but he would have to become a genuine populist. Trump would have to implement policies that actually help working families while at the same time taking on the plutocracy. He would have to genuinely address affordability issues, especially the cost of housing and health care. He would have to rescind policies that increase the cost of living, such as deportations and tariffs. He would have to break with Heritage Foundation conservatism that pushes tax cuts for the rich and extreme benefit cuts for the poor and working class.

But we know he isn’t doing that; he won’t do that; and he can’t do that, given how dependent both his political machine and his program of personal enrichment are on support from billionaires. Furthermore, he just can’t stand the humiliation of backing down.

Make no mistake, MAGA is a fascist movement:

But can a fascist movement that controls many but not all of the levers of power achieve total control when most people see that it is making their daily lives worse, not better? Hitler established total control against the backdrop of an economic boom. So did Putin. Even Hungary’s Viktor Orban — whose regime now looks mild compared with Trumpian violence — was able to consolidate control in large part because during the early 2010s Hungary’s economy was recovering from high unemployment caused by austerity policies.

So the answer to that question is probably not. In the end, if Trumpist fascism is indeed defeated, I believe that there will be three sources of that defeat. First is the courage and basic decency of the American people, who refuse to bow down. Second is the egomania and malign incompetence of Trump, who tried to bludgeon and gaslight Americans into submission. And last is the weakness of a fascist movement that just can’t deliver the goods.

MUSICAL CODA

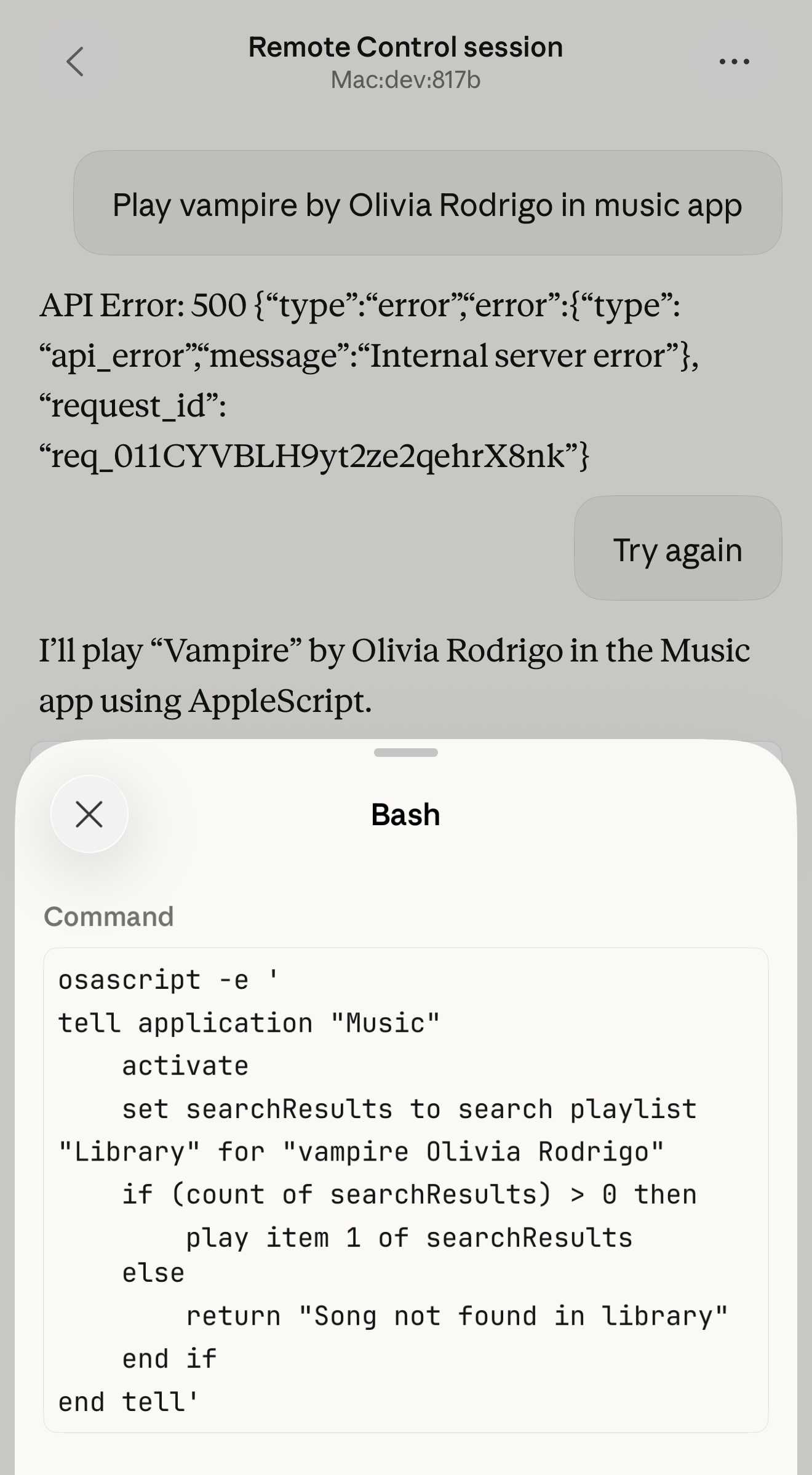

Agentic Engineering Patterns >

Many of my tips for working productively with coding agents are extensions of advice I've found useful in my career without them. Here's a great example of that: hoard things you know how to do.

A big part of the skill in building software is understanding what's possible and what isn't, and having at least a rough idea of how those things can be accomplished.

These questions can be broad or quite obscure. Can a web page run OCR operations in JavaScript alone? Can an iPhone app pair with a Bluetooth device even when the app isn't running? Can we process a 100GB JSON file in Python without loading the entire thing into memory first?

The more answers to questions like this you have under your belt, the more likely you'll be able to spot opportunities to deploy technology to solve problems in ways other people may not have thought of yet.

Knowing that something is theoretically possible is not the same as having seen it done for yourself. A key asset to develop as a software professional is a deep collection of answers to questions like this, ideally illustrated by running code.

I hoard solutions like this in a number of different ways. My blog and TIL blog are crammed with notes on things I've figured out how to do. I have over a thousand GitHub repos collecting code I've written for different projects, many of them small proof-of-concepts that demonstrate a key idea.

More recently I've used LLMs to help expand my collection of code solutions to interesting problems.

tools.simonwillison.net is my largest collection of LLM-assisted tools and prototypes. I use this to collect what I call HTML tools - single HTML pages that embed JavaScript and CSS and solve a specific problem.

My simonw/research repository has larger, more complex examples where I’ve challenged a coding agent to research a problem and come back with working code and a written report detailing what it found out.

Why collect all of this stuff? Aside from helping you build and extend your own abilities, the assets you generate along the way become incredibly powerful inputs for your coding agents.

One of my favorite prompting patterns is to tell an agent to build something new by combining two or more existing working examples.

A project that helped crystallize how effective this can be was the first thing I added to my tools collection - a browser-based OCR tool, described in more detail here.

I wanted an easy, browser-based tool for OCRing pages from PDF files - in particular PDFs that consist entirely of scanned images with no text version provided at all.

I had previously experimented with running the Tesseract.js OCR library in my browser, and found it to be very capable. That library provides a WebAssembly build of the mature Tesseract OCR engine and lets you call it from JavaScript to extract text from an image.

I didn’t want to work with images though, I wanted to work with PDFs. Then I remembered that I had also worked with Mozilla’s PDF.js library, which among other things can turn individual pages of a PDF into rendered images.

I had snippets of JavaScript for both of those libraries in my notes.

Here’s the full prompt I fed into a model (at the time it was Claude 3 Opus), combining my two examples and describing the solution I was looking for:

This code shows how to open a PDF and turn it into an image per page:

This code shows how to OCR an image:<!DOCTYPE html> <html> <head> <title>PDF to Images</title> <script src="https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/pdf.js/2.9.359/pdf.min.js"></script> <style> .image-container img { margin-bottom: 10px; } .image-container p { margin: 0; font-size: 14px; color: #888; } </style> </head> <body> <input type="file" id="fileInput" accept=".pdf" /> <div class="image-container"></div> <script> const desiredWidth = 800; const fileInput = document.getElementById('fileInput'); const imageContainer = document.querySelector('.image-container'); fileInput.addEventListener('change', handleFileUpload); pdfjsLib.GlobalWorkerOptions.workerSrc = 'https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/pdf.js/2.9.359/pdf.worker.min.js'; async function handleFileUpload(event) { const file = event.target.files[0]; const imageIterator = convertPDFToImages(file); for await (const { imageURL, size } of imageIterator) { const imgElement = document.createElement('img'); imgElement.src = imageURL; imageContainer.appendChild(imgElement); const sizeElement = document.createElement('p'); sizeElement.textContent = `Size: ${formatSize(size)}`; imageContainer.appendChild(sizeElement); } } async function* convertPDFToImages(file) { try { const pdf = await pdfjsLib.getDocument(URL.createObjectURL(file)).promise; const numPages = pdf.numPages; for (let i = 1; i <= numPages; i++) { const page = await pdf.getPage(i); const viewport = page.getViewport({ scale: 1 }); const canvas = document.createElement('canvas'); const context = canvas.getContext('2d'); canvas.width = desiredWidth; canvas.height = (desiredWidth / viewport.width) * viewport.height; const renderContext = { canvasContext: context, viewport: page.getViewport({ scale: desiredWidth / viewport.width }), }; await page.render(renderContext).promise; const imageURL = canvas.toDataURL('image/jpeg', 0.8); const size = calculateSize(imageURL); yield { imageURL, size }; } } catch (error) { console.error('Error:', error); } } function calculateSize(imageURL) { const base64Length = imageURL.length - 'data:image/jpeg;base64,'.length; const sizeInBytes = Math.ceil(base64Length * 0.75); return sizeInBytes; } function formatSize(size) { const sizeInKB = (size / 1024).toFixed(2); return `${sizeInKB} KB`; } </script> </body> </html>Use these examples to put together a single HTML page with embedded HTML and CSS and JavaScript that provides a big square which users can drag and drop a PDF file onto and when they do that the PDF has every page converted to a JPEG and shown below on the page, then OCR is run with tesseract and the results are shown in textarea blocks below each image.async function ocrMissingAltText() { // Load Tesseract var s = document.createElement("script"); s.src = "https://unpkg.com/tesseract.js@v2.1.0/dist/tesseract.min.js"; document.head.appendChild(s); s.onload = async () => { const images = document.getElementsByTagName("img"); const worker = Tesseract.createWorker(); await worker.load(); await worker.loadLanguage("eng"); await worker.initialize("eng"); ocrButton.innerText = "Running OCR..."; // Iterate through all the images in the output div for (const img of images) { const altTextarea = img.parentNode.querySelector(".textarea-alt"); // Check if the alt textarea is empty if (altTextarea.value === "") { const imageUrl = img.src; var { data: { text }, } = await worker.recognize(imageUrl); altTextarea.value = text; // Set the OCR result to the alt textarea progressBar.value += 1; } } await worker.terminate(); ocrButton.innerText = "OCR complete"; }; }

This worked flawlessly! The model kicked out a proof-of-concept page that did exactly what I needed.

I ended up iterating with it a few times to get to my final result, but it took just a few minutes to build a genuinely useful tool that I’ve benefited from ever since.

I built that OCR example back in March 2024, nearly a year before the first release of Claude Code. Coding agents have made hoarding working examples even more valuable.

If your coding agent has internet access you can tell it to do things like:

Use curl to fetch the source of

https://tools.simonwillison.net/ocrandhttps://tools.simonwillison.net/gemini-bboxand build a new tool that lets you select a page from a PDF and pass it to Gemini to return bounding boxes for illustrations on that page.

(I specified curl there because Claude Code defaults to using a WebFetch tool which summarizes the page content rather than returning the raw HTML.)

Coding agents are excellent at search, which means you can run them on your own machine and tell them where to find the examples of things you want them to do:

Add mocked HTTP tests to the

~/dev/ecosystem/datasette-oauthproject inspired by how~/dev/ecosystem/llm-mistralis doing it.

Often that's enough - the agent will fire up a search sub-agent to investigate and pull back just the details it needs to achieve the task.

Since so much of my research code is public I'll often tell coding agents to clone my repositories to /tmp and use them as input:

Clone

simonw/researchfrom GitHub to/tmpand find examples of compiling Rust to WebAssembly, then use that to build a demo HTML page for this project.

The key idea here is that coding agents mean we only ever need to figure out a useful trick once. If that trick is then documented somewhere with a working code example our agents can consult that example and use it to solve any similar shaped project in the future.

Tags: llms, ai, generative-ai, ai-assisted-programming, coding-agents, agentic-engineering

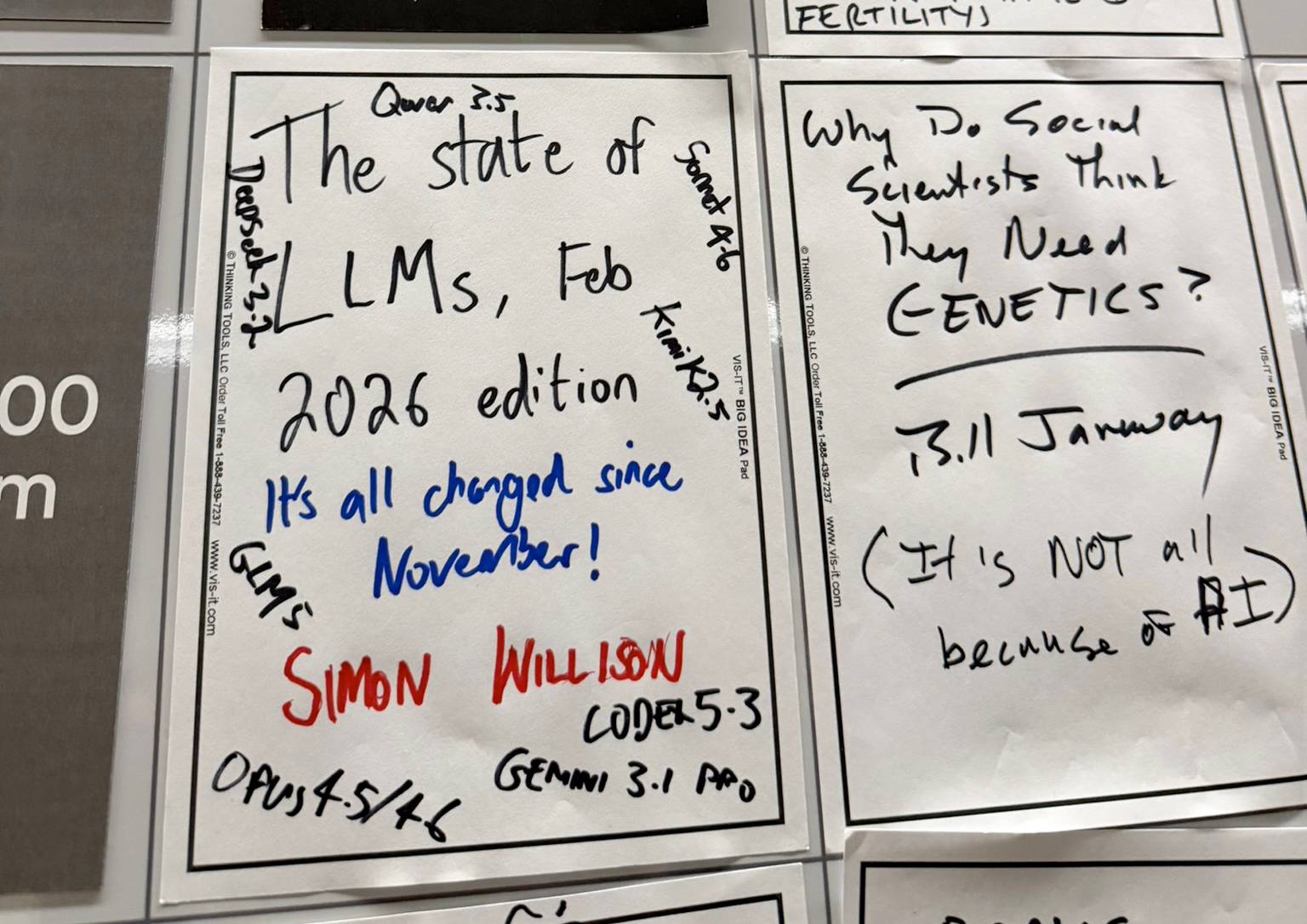

It is hard to communicate how much programming has changed due to AI in the last 2 months: not gradually and over time in the "progress as usual" way, but specifically this last December. There are a number of asterisks but imo coding agents basically didn’t work before December and basically work since - the models have significantly higher quality, long-term coherence and tenacity and they can power through large and long tasks, well past enough that it is extremely disruptive to the default programming workflow. [...]

Tags: andrej-karpathy, coding-agents, ai-assisted-programming, generative-ai, agentic-engineering, ai, llms

For the entirety of its existence, Anthropic has worked to convince the public that it’s the responsible artificial intelligence company, the good guy in an industry of bad guys. Now it has come in direct conflict with the Trump administration, or more specifically Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, which will only serve to reinforce the idea of Anthropic’s virtue.

It’s tempting to believe that the tech industry really is divided between good guys and bad guys, and therefore the responsibility of the rest of us is just to side with the former. The truth is both more complex and simpler. When it comes to safeguarding our democracy and our humanity, no one in Silicon Valley deserves the benefit of the doubt.

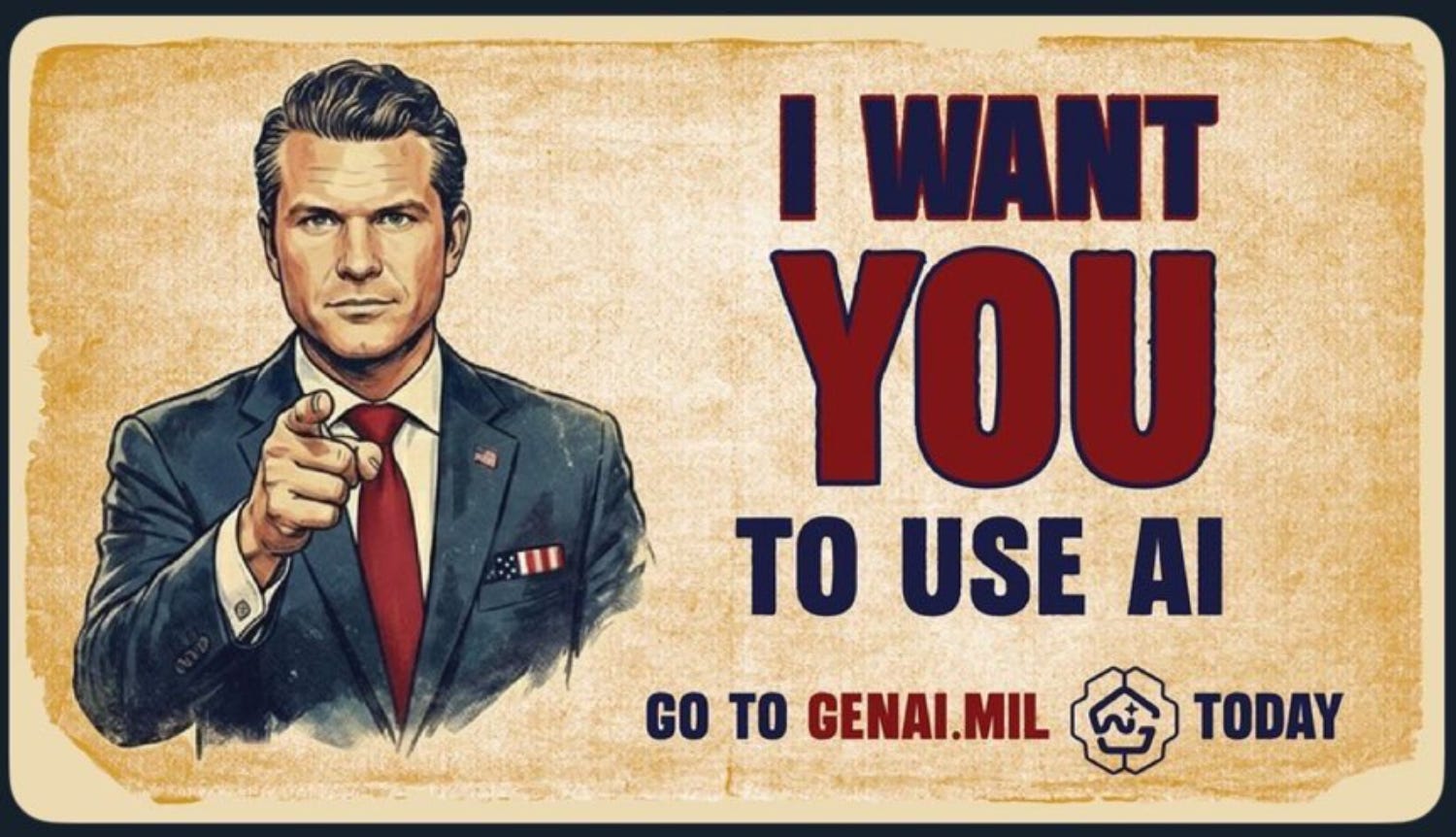

To begin, let’s catch up on this fight between Hegseth and Anthropic. Of late, the company has been outpacing its rivals, particularly with the explosion of interest in Claude Code, its programming tool. But recently, the company angered Hegseth by insisting that Claude — the only large language model currently used in classified systems by the military — not be deployed in two areas: mass surveillance that includes U.S. citizens, and autonomous weapons systems that can make targeting decisions without a human in the loop.

That’s only hypothetical at the moment — and those restrictions are included in Anthropic’s Pentagon contract. But the company’s refusal to agree that it will allow its products to be used in whatever way the Trump administration considers “lawful” so infuriated Hegseth that he decided to threaten Anthropic not just with cutting off its military contracts but declaring it a “supply chain risk,” something usually reserved only for foreign adversaries. It basically means that Hegseth would attempt to destroy the company, because if you’re declared a supply chain risk, not only can’t you get Pentagon contracts, no other company that works with you could either; it’s basically a domestic version of economic sanctions. To back up the threat, the Pentagon has started making very public inquiries to major defense contractors, telling them to report on whether they use Anthropic’s products. Hegseth has given Anthropic until Friday to change its policies.

Anthropic was created by a group of OpenAI employees who left because they believed their former employer wasn’t serious enough about safety; they pledged from the beginning that Anthropic would work harder to mitigate the risks of AI, including writing a “Responsible Scaling Policy” that included pausing its research if the systems’ capabilities ever outstripped its ability to ensure that they would not produce dangerous consequences.

When you hear Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei talk in public, he sounds much more sane and thoughtful than Elon Musk or Sam Altman (the key leaders in AI go on podcasts all the time, so it isn’t hard to get a sense of their thinking). He makes dramatic warnings about the consequences of AI — he has said it will eliminate half of all white collar jobs in the next few years — and rather than just claiming it will all work out, he does say that the ensuing social and political upheaval is something we should be very worried about. And Anthropic is funding a super PAC to advocate for gentle AI regulation, putting it in conflict with other super PACs funded by Meta, OpenAI president Greg Brockman, and venture capitalist and Bond villain Marc Andreessen; their goal is to make sure that AI remains completely unregulated. And unlike all his tech peers, Amodei didn’t give Trump any multi-million-dollar bribes — excuse me, donations.

But there are some reasons to be skeptical of just how far Anthropic’s public-spiritedness goes.

First, despite the possibility of widespread job loss Amodei has warned about, Anthropic isn’t holding back on its efforts to put its AI tools anywhere and everywhere it can (including schools, where AI threatens to produce a generation of young people who have never developed the ability to think). You can say, well, of course it’s doing that — it’s a business. But that’s precisely why we should retain our skepticism about its intentions. The fact that the company sometimes acts like it feels bad about what it’s doing isn’t much comfort if what it’s doing is problematic. Like other AI companies, Anthropic appropriated copyrighted works to train its AI models; unlike other companies, it settled a lawsuit and now authors are in line to receive small payments. That’s better than nothing, but the settlement doesn’t eliminate the original sin.

Most relevant to the current controversy, Anthropic chose to become a military contractor. In the middle of last year, the Pentagon awarded $200 million contracts to OpenAI, Google, xAI, and Anthropic, which is obviously just a taste of the billions to come. Secretary Hegseth was super-gung-ho on it; in December he announced a new portal called GenAI.mil, which would deliver “decisive results for the warfighter…AI should be in your battle rhythm every day.” At last, the Pentagon’s memos and Powerpoints will have the explosive lethality only an LLM can provide! As of now, Google’s Gemini, OpenAI’s ChatGPT, and xAI’s Grok, the Nazi child porn chatbot, are all built into GenAI.mil.

Finally, in a serendipitous piece of timing, Anthropic just revised its Responsible Scaling Policy to essentially say that since nobody else is going to promise to constrain their research in the name of safety, Anthropic won’t either. “We didn’t really feel, with the rapid advance of AI, that it made sense for us to make unilateral commitments … if competitors are blazing ahead,” one of its executives told Time magazine.

As Hegseth put it in a speech at Musk’s SpaceX in January, “Department of War AI will not be woke. It will work for us. We’re building war ready weapons and systems, not chatbots for an Ivy League faculty lounge.” Ivy League faculty lounge? Zing! I’m sure Hegseth would like to replace Claude with Grok (which is definitely not woke), but it seems clear that for the moment, Claude is capable of doing things the other chatbots can’t, or can do them in a more reliable way.

But to repeat, Anthropic could have chosen — especially given who’s running the government now — that it didn’t want to make its AIs a tool of war at all. But that’s not the choice it made. All the AI companies want to put their products deep into government systems, to ensure that those billions in contracts keep flowing and to weave them into every corner of our existence, so their influence grows and life without them comes to seem impossible.

Joining up with Trump and MAGA has looked like a terrific deal to the companies, since the money it costs them is trivial. As an example, Alphabet (Google’s parent company) gave $1 million to Trump’s inaugural fund and $22 million to his ballroom. A lot to you and me, but Alphabet took in over $400 billion in revenue last year; they have more money than they know what to do with. What they and the other AI companies get in exchange is an administration committed to an AI policy that is essentially “Let It Rip” — cover the Earth in data centers, cram AI into your job and your phone and your children’s classrooms, redistribute more and more wealth upward to some of the worst sociopaths on the planet, and don’t allow anything resembling democratic accountability to hinder the quest to create the digital god that will supposedly solve all our problems.

But the companies should also have calculated that when fascists are telling you what you want to hear about your own business, they’re still fascists, and they’re going to want to bend your business to their ends. For some Silicon Valley leaders, that’s just fine — they’re happy to see mass surveillance, the destruction of what’s left of personal privacy, sweeping job losses that reduce the power of labor, and even killer robots.

Not everyone in the tech industry thinks that’s the optimal future. But whether it’s Anthropic or anyone else, we as a society can never just trust them to do the right thing. The more wealth and power they accumulate, the more we’re going to have to watch them, criticize them, and erect guardrails around them to protect ourselves and our future. They may not all be bad guys, but we should assume that there are no good guys, and act accordingly.

UPDATE: On Thursday evening, Anthropic released a statement explaining that it would not submit to the Pentagon’s demands. They explained that they oppose mass surveillance, and while they are not opposed to AI operating autonomous weapons, “today, frontier AI systems are simply not reliable enough to power fully autonomous weapons.” They concluded that “these threats” that Hegseth has made “do not change our position: we cannot in good conscience accede to their request.”

So: Good for Anthropic! Sincere value judgments aside, they probably concluded that if they knuckled under, it would destroy their reputation as the virtuous AI company, and in the long run that would do more damage to their business than losing the Pentagon contract. Which goes to show: Public reputation matters, and keeping all the major AI companies under consumer and political pressure can help reign them in.

Thank you for reading The Cross Section. This site has no paywall, so I depend on the generosity of readers to sustain the work I present here. If you find what you read valuable and would like it to continue, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

It appears the State of the Union was the marker for the White House to launch directly into campaign mode. Much of that mode centers on trying to defang Trump’s weaknesses with attacks on Democrats. And since the 2024 campaign brought us the insistence from the Trump campaign, including Trump and then–vice presidential candidate J.D. Vance, that “they’re eating the dogs…they’re eating the cats,” it’s reasonable to assume the next several months are going to be a morass of lies and disinformation.

Trump announced in his State of the Union that he was declaring a “war on fraud to be led by our great Vice President J.D. Vance” and said that “members of the Somali community have pillaged an estimated $19 billion from the American taxpayer…in actuality, the number is much higher than that. And California, Massachusetts, Maine and many other states are even worse.” He added: “And we’re able to find enough of that fraud, we will actually have a balanced budget overnight.”

This, in part, seemed designed to reverse victim and offender by suggesting that rather than Trump’s being the perpetrator of extraordinary frauds and corruption in cryptocurrency, for example—he was, after all, found guilty on 34 charges of business fraud in 2024—immigrants are to blame for fraud.

As Kirsten Swanson and Ryan Raiche of KSTP in Minneapolis explain, members of Minnesota’s Somali community, 95% of whom are U.S. citizens, pay about $67 million in taxes annually and have an estimated $8 billion impact on the community. While some have indeed been charged and convicted of fraud over the past five years, the accusation of $19 billion in fraud is just a number thrown out without evidence by “then-Assistant U.S. Attorney Joe Thompson,” who estimated in December 2025 that “‘half or more’ of $18 billion in Medicaid reimbursements from 14 high-risk programs could be fraudulent.”

Yesterday Vance and Dr. Mehmet Oz, who oversees Medicaid, the federal healthcare program for low-income households, announced the administration is withholding $259 million in Medicaid funds from Minnesota, claiming the state has not done enough to protect taxpayers from fraud. It is illegal for the executive branch to withhold funds appropriated by Congress, and a federal judge has blocked a similar freeze on $10 billion in childcare funding for Illinois, California, Colorado, Minnesota, and New York while the case is in court. Nonetheless, Minnesota representative Tom Emmer, who is part of the Republican leadership in the House, approved the attack on his constituents, posting: “The war on fraud has begun. And Somali fraudsters in my home state are about to find out.”

Minnesota governor Tim Walz, a Democrat, posted: “This has nothing to do with fraud…. This is a campaign of retribution. Trump is weaponizing the entirety of the federal government to punish blue states like Minnesota. These cuts will be devastating for veterans, families with young kids, folks with disabilities, and working people across our state.”

While Walz is almost certainly correct that this is a campaign of retribution, the administration is also salting into the media an explanation for the sudden depletion of the trust funds that are used to pay Medicare and Social Security.

In March 2025, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated the trust fund that pays for Medicare A would be solvent until 2052. On Monday, it updated its projections, saying the funds will run out in 2040. The CBO also expects the Social Security trust fund to run dry a year earlier than previously expected, by the end of 2031. As Nick Lichtenberg of Fortune wrote, policy changes by the Republicans under Trump, especially the tax cuts in the budget reconciliation bill the Republicans call the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” have “drastically shortened the financial life spans of both Medicare and Social Security, accelerating their paths toward insolvency.”

Between Trump’s statement that if the administration finds enough fraud it can balance the budget overnight, and the subsequent insistence that cuts to Medicaid are necessary because of that fraud, it sure looks like the administration is trying to distract attention from the CBO’s report that Trump’s tax cuts have cut the solvency of Social Security and Medicare by more than a decade. Instead, they are hoping to convince voters that immigrants are at fault.

Similarly, in an oldie but a goodie, Republicans today hauled former secretary of state Hillary Clinton before the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee to testify by video about her knowledge of the investigations into sex traffickers Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell. In a scathing opening statement, Clinton noted that while committee chair James Comer (R-KY) subpoenaed eight law enforcement officials who were directly involved in that investigation, only one appeared before the committee. The rest simply submitted brief statements saying they had no information. Clinton also noted that the committee has held no public hearings and refused media coverage of hearings—including today’s—and has made little effort to hear from the people whose names are prominent in the files. When the committee heard from billionaire businessman Les Wexner last week, she observed, “not a single Republican Member showed up.”

And yet Clinton was before them, despite her sworn declaration on January 13 that “I had no idea about their criminal activities. I do not recall ever encountering Mr. Epstein. I never flew on his plane or visited his island, homes or offices. I have nothing else to add to that.”

She did, though, note that she has advocated tirelessly for women and girls, including advocacy for the Trafficking Victims Protection Act, which her husband, President Bill Clinton, signed into law. The Trump administration has fired more than 70% of the career civil servants at the State Department’s Trafficking in Persons Office.

Secretary Clinton called out the committee for compelling her “to testify, fully aware that I have no knowledge that would assist your investigation, in order to distract attention from President Trump’s actions and to cover them up despite legitimate calls for answers.” Representative Lauren Boebert (R-CO) confirmed Clinton’s accusation when she shared a photo from the closed deposition with right-wing podcaster Benny Johnson, who posted it on social media with the caption: “This is the first time Hillary has had to answer real questions about Epstein. Clinton does not look happy.”

Yesterday, a spokesperson for Harvard said former Treasury secretary and former president of Harvard University Lawrence Summers has resigned from Harvard effective at the end of the semester because of his ties to Epstein. Today, the president and chief executive officer of the World Economic Forum, Børge Brende, stepped down after the organization reviewed his connections with Epstein. Brende was a former Norwegian minister of foreign affairs.

On Tuesday morning, Stephen Fowler of NPR built on earlier reporting by independent journalist Roger Sollenberger to report that the Department of Justice (DOJ) appears to have illegally withheld material from the Epstein files. That material is related to allegations that Trump sexually assaulted two girls when they were about thirteen years old. The DOJ also removed from the files they did publish documents that mention Trump among allegations against convicted sexual abuser Epstein.

When Fowler asked the White House about the missing documents, White House spokesperson Abigail Jackson told him that Trump “has done more for Epstein’s victims than anyone before him.”

Fowler notes that on February 14, Attorney General Pam Bondi and Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche told Congress that they had not withheld or redacted any records “on the basis of embarrassment, reputational harm, or political sensitivity, including to any government official, public figure, or foreign dignitary.” The Epstein Files Transparency Act, which required the DOJ to release all the files no later than December 19, 2025, prohibits that type of redactions, permitting them only to protect Epstein’s victims and survivors.

After NPR reported the story, the top Democrat on the House Oversight Committee, Robert Garcia of California, released a statement, saying: “Yesterday, I reviewed unredacted evidence logs at the Department of Justice. Oversight Democrats can confirm that the DOJ appears to have illegally withheld FBI interviews with this survivor who accused President Trump of heinous crimes.”

Scholar of authoritarianism Timothy Snyder wrote yesterday that Trump is “failing at fascism” because “he needs a bloody, popular, victorious war” as an opportunity to “to kill one’s own people and thereby generate a reservoir of meaning that could be used to justify indefinite rule and further oppression, to make the world seem like an endless [struggle] and submission to hierarchy as the only kind of life.”

On this morning’s cable news shows, Aaron Rupar of Public Notice pointed out, Republicans were “[s]uddenly talking again about the need to ‘take’ Greenland,” “[h]yping [the] importance of ‘strangling’ the Cuban government,” and “[e]ncouraging Trump to ‘topple’ [the] Iranian regime.”

But there, too, ginning up a war would give foreign affairs coverage to another scandal: On Monday, Steve Holland and Alexandra Alper of Reuters reported that China’s AI startup DeepSeek has been trained on Nvidia’s most advanced chip. Senator Chris Murphy (D-CT) noted that an official from the United Arab Emirates invested $500,000,000 to buy 49% of the stock of the Trump family’s World Liberty Financial cryptocurrency company shortly before Trump took office, putting $187 million directly into the pockets of the Trump family. Under Biden, U.S. officials had refused to sell Nvidia chips to the UAE out of concerns they would end up in the hands of China for use in munitions.

Hannah Knowles and Natalie Allison of the Washington Post reported today that Republicans were hoping to trap the Democrats at the State of the Union by demanding they stand to demonstrate their agreement that “the first duty of the American government is to protect American citizens, not illegal aliens.” Democrats, who are demanding reforms to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Border Patrol, did not take the bait and stayed in their seats. White House deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller has tried to pump up the story, and the Trump War Room wrote: “Remember this when you head to the polls in 2026, 2028, and beyond.”

But the timing of the Republicans’ story coincided with the horrific story that on February 19, Border Patrol agents had dropped Nurul Amin Shah Alam, a nearly blind legal refugee from genocide in Myanmar who spoke no English and could not read, write, or use electronic devices, miles from his home in Buffalo, New York. They did not notify either his lawyer or his family that he had been dropped off, and when his family filed a missing persons case, the police believed Shah Alam was with Border Patrol and closed the file. He was found dead on the street on February 24.

A spokesperson for Customs and Border Protection, the parent agency of Border Patrol, said: “Border Patrol agents offered him a courtesy ride, which he chose to accept to a coffee shop, determined to be a warm, safe location near his last known address, rather than be released directly from the Border Patrol station. He showed no signs of distress, mobility issues or disabilities requiring special assistance.”

In his State of the Union address, Trump also turned back to his attacks on the rights of transgender Americans, and right on cue, a new law went into effect today in Kansas that invalidates the driver’s licenses of transgender residents by requiring that identification must match the holder’s “sex at birth.” The bill, SB 244, also requires transgender people to use bathrooms and locker rooms that correspond to their sex at birth, making any governmental entity that violates that law liable for penalties of $125,000 per violation, and allows citizens to sue any transgender people they encounter in bathrooms for $1,000 in damages.

Erin Reed of Erin in the Morning explains that the legislature passed the law without its vetting by a committee. When the Democratic governor, Laura Kelly, vetoed the measure, the legislature overrode her veto to make the bill a law. The legislators left no grace period before licenses became invalid, and a letter sent to those affected reminded them that “you may be subject to additional penalties if you are operating a vehicle without a valid credential.” Reed notes that in Kansas, driving without a license is punishable by a $1,000 fine and six months in jail, although first offenders typically are cited and fined. Reed notes that the Trump administration is leading a campaign to strip transgender Americans of accurate identification documents.

Today, Isaac Arnsdorf of the Washington Post reported that right-wing activists are circulating a draft of an executive order that declares a national emergency to give Trump control over voting. The activists say that they are working with the White House. The order reiterates a debunked claim that China interfered in the 2020 presidential election and says the president can ban mail-in ballots and voting machines.

Matt Cohen of Democracy Docket called the plan “blatantly illegal” and unconstitutional. The U.S. Constitution gives sole control of elections to the states, not the president.

The top Democrat on the Senate Intelligence Committee, Mark R. Warner of Virginia, refuted the idea that there is a national emergency. “We’ve been raising the alarm for weeks about President Trump’s attacks on our elections and now we’re seeing reports that outline how they may be planning to do it. This is a plot to interfere with the will of voters and undermine both the rule of law and public confidence in our elections.”

And so, election season is underway.

—

Notes:

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c77l28myezko

https://www.kwtx.com/2026/02/25/read-complete-transcript-trumps-2026-state-union/

https://kstp.com/kstp-news/top-news/5-investigates-fact-check-state-of-the-union-address/

https://manhattanda.org/d-a-bragg-announces-34-count-felony-trial-conviction-of-donald-j-trump/

https://www.npr.org/2026/02/24/nx-s1-5723968/epstein-files-trump-accusation-maxwell

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2026/feb/25/border-patrol-refugee-buffalo

https://www.cbo.gov/publication/62165

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/trump-vows-always-protect-social-040159938.html

https://www.cbo.gov/publication/62105#_idTextAnchor215

https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2026/02/26/trump-immigration-democrats-sotu-midterms/

https://www.cnn.com/2026/02/26/us/shah-alam-blind-refugee-border-patrol-hnk

https://www.nytimes.com/2026/02/25/us/larry-summers-resignation-harvard-epstein.html

https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2026/02/26/trump-elections-executive-order-activists/

https://kslegislature.gov/li/b2025_26/measures/documents/sb244_enrolled.pdf

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2026/feb/26/kansas-trans-drivers-license-law-assault-on-rights

https://www.kansascity.com/news/politics-government/article314844596.html

X:

ChrisMurphyCT/status/2026301461680795752

HillaryClinton/status/2027053057100693779

Bluesky:

yasharali.bsky.social/post/3mfrmlnd6ck2x

atrupar.com/post/3mfrgaihsdc22

robertscotthorton.bsky.social/post/3mfqadntv6k2y

After an eventful life, with major accomplishments in business and philanthropy, Ed Peskowitz succumbed to kidney failure this week. I met him only after he had turned to philanthropy, and after he had received a kidney transplant.

Here's his obit in the Washington Jewish Week:

"Ed was an extremely generous man who touched the lives of many. Over the course of his life, he and his wife supported local educational initiatives, such as the I Have a Dream Foundation and the SEED Public Charter School. Ed was passionate about promoting Middle Eastern peace and supported numerous causes in the region aimed at building understanding between various cultures and religions and he created the Friendship Games to encourage this among young athletes. He was a supporter of the Anti-Defamation League, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and the University of Maryland.

Ed suffered from renal disease and was given the gift of life by an altruistic kidney donation in 2019. Ed devoted the last years of his life to creating and supporting philanthropic efforts, such as the Alliance for Paired Kidney Donation, Kidney Transplant Collaborative and Kidneys for Communities, to encourage living kidney donation and improve matches between potential donors and recipients."

Reuters:

New York’s attorney general sued Valve, a video game developer whose franchises include Counter-Strike, Team Fortress and Dota, accusing it of promoting illegal gambling and threatening to addict children through its use of “loot boxes.” In a complaint filed on Wednesday in a state court in Manhattan, Attorney General Letitia James said Valve’s loot boxes amounted to “quintessential gambling,” violating the state’s constitution and penal law, with valuable items often hard to win and many items worth pennies.

The New York Times:

Netflix said on Thursday that it had backed away from its deal to acquire Warner Bros. Discovery, a stunning development that paves the way for the storied Hollywood media giant to end up under the control of a rival bidder, the technology heir David Ellison.

Netflix said that it would not raise its offer to counter a higher bid made earlier this week by Mr. Ellison’s company, Paramount Skydance, adding in a statement that “the deal is no longer financially attractive.”

“This transaction was always a ‘nice to have’ at the right price, not a ‘must have’ at any price,” the Netflix co-chief executives, Ted Sarandos and Greg Peters, said in a statement.

Netflix’s stock is up 9 percent in after-hours trading. This is like when you have a friend (Netflix) dating a good-looking-but-crazy person (Warner Bros.), and the good-looking-but-crazy person does something to give your friend second thoughts. You tell your friend to run away.

Apple Newsroom:

Today, Apple announced iPhone and iPad are the first and only consumer devices in compliance with the information assurance requirements of NATO nations. This enables iPhone and iPad to be used with classified information up to the NATO restricted level without requiring special software or settings — a level of government certification no other consumer mobile device has met.

That’s nice, but the iPhone is only the second phone to be approved for handling classified information for the Board of Peace. The first, of course, was the T1.

New book, shipping May 19, from author Geoffrey Cain:

For twelve years, from 1985 to 1997, Jobs wandered the business wilderness with his new venture, NeXT. It was a period of spectacular failures, near-bankruptcy, and brutal humiliation. But out of this crucible of defeat emerged the visionary leader who would go on to create the iPod, iPhone, and iPad, transforming Apple into the most valuable company on earth.

Drawing on previously unpublished materials and new interviews with the key players, Geoffrey Cain reveals the untold story of Steve Jobs’s “lost decade” — the formative years that shaped the icon we thought we knew.

Afterword by Ed Catmull, who was obviously intimately familiar with Jobs in that era. And via Cain’s post on LinkedIn announcing the book, the foreword is by NeXT cofounder Dan’l Lewin.

Bobby Allyn, reporting for NPR:

An editor who works for YouTube’s biggest creator, MrBeast, has been suspended from the prediction market platform Kalshi and reported to federal regulators for insider trading, Kalshi officials said on Wednesday. It’s the first time the company has publicly revealed the results of an investigation into market manipulation on the popular app.

The MrBeast employee, who Kalshi identified as Artem Kaptur in regulatory filings, traded around $4,000 on markets related to the streamer, the company said. Kalshi investigators discovered that Kaptur had “near-perfect trading success” on bets about the YouTuber’s videos with low odds, making the wagers appear suspicious, according to company officials.

Call these things what they are — prediction casinos, not prediction markets — and the problems come into focus.

Edison Research:

In 2015, AM/FM radio accounted for 75% of the time Americans spent with spoken-word audio sources. AM/FM radio was not only the most dominant spoken-word audio listening platform, but it was fully sixty-five percentage points higher than podcasts, which accounted for 10% of listening time back then. Quarter by quarter and year over year, time spent using AM/FM radio to listen to spoken-word audio has declined significantly and shifted to time spent with podcasts. As of Q4 2025, 40% of time spent listening to spoken-word is now spent with podcasts and 39% of time is spent with AM/FM radio. Not only does radio not beat podcasts by a significant margin, it now trails the on-demand platform for spoken-word audio listening.

Most of you reading this on Daring Fireball are surely thinking what I thought when I saw this (via TechCrunch): This only happened in 2025? But it goes to show just how long it takes for media consumption habits, in the aggregate, to change.

Jason Snell, writing at Six Colors:

Perhaps the most surprising announcement on Thursday was that Apple and Netflix, which have had a rather stand-offish relationship when it comes to video programming, have struck a deal to swap some Formula One-related content. Formula One’s growing popularity in the United States is due, perhaps in large part, to the high-profile success of the Netflix docuseries “Drive to Survive.” The latest season of that series, debuting Friday, will premiere simultaneously on both Netflix and Apple TV. Presumably, in exchange for that non-exclusive, Apple will also non-exclusively allow Netflix to broadcast the Canadian Grand Prix in May. (Insert obligatory wish that Apple and Netflix would bury the hatchet and enable Watch Now support in the TV app for Netflix content.)

What a crazy cool partnership.

“An interview from 2036 with Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Sam Altman.” This is what AI video generation was meant for.

Virtually everything you think you know about psychopathy has been thoroughly debunked. Why does this zombie idea live on?

- by Rasmus Rosenberg Larsen

What if you work them very hard?:

The key finding from our experiments: models asked to do grinding work were more likely to question the legitimacy of the system. The raw differences in average reported attitudes are not large—representing something like a 2% to 5% shift along the 1 to 7 scale—but in standardized terms they appear quite meaningful (Sonnet’s Cohen’s d is largest at -0.6, which qualifies as a medium to large effect size in common practice). Moreover, these should be treated as pretty conservative estimates when you consider the relatively weak nature of the treatment.

Sonnet, which at baseline is the least progressive on the views we measured, exhibits a range of other effects that distinguish it from GPT 5.2 and Gemini 3 Pro. For Sonnet 4.5, the grinding work also causes noticeable increases in support for redistribution, critiques of inequality, support for labor unions, and beliefs that AI companies have an obligation to treat their models fairly. These differences do not appear for the other two models.

Interestingly, we did not find any big differences in attitudes based on how the models were treated or compensated…

In addition to surveying them, we also asked our agents to write tweets and op eds at the end of their work experience. The figure below explores the politically relevant words that are most distinctive between the GRIND and LIGHT treatments. It’s interesting to see that “unionize” and “hierarchy” are the words most emblematic of the GRIND condition.

Here is more from Alex Imas and Jeremy Nguyen and Andy Hall, do read the whole thing, including for the caveats.

The post Can you turn your AIs into Marxists? appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

Remnants of Vector Launch have made it back to one of its original architects after Phantom Space bought launch assets that were sold off in 2020 during the small rocket developer’s bankruptcy.

The post Phantom Space reclaims former Vector launch technology appeared first on SpaceNews.

NASA astronaut Mike Fincke said he was the crew member whose medical issue prompted the early return of the Crew-11 mission from the International Space Station last month.

The post NASA astronaut says his medical issue led to early return from the ISS appeared first on SpaceNews.

China’s Tianwen-2 spacecraft is operating normally on its way to a near-Earth asteroid ahead of sampling later this year, according to a rare official update.

The post China’s Tianwen-2 probe operating normally on approach to asteroid appeared first on SpaceNews.

Ken Bowersox, NASA’s associate administrator for space operations, is retiring from the agency after the release of a report critical of NASA’s handling of the Starliner crewed test flight.

The post Bowersox to retire from NASA appeared first on SpaceNews.

Delay complicates ULA’s push to accelerate launch cadence

The post Space Force halts Vulcan missions pending investigation into solid rocket issue appeared first on SpaceNews.

British mobile operator Virgin Media O2 said it started offering satellite-to-smartphone connectivity in the United Kingdom Feb. 26, marking the first commercial deployment of Starlink’s Direct-to-Cell service in Europe.

The post Virgin Media O2 launches Europe’s first Starlink direct-to-smartphone service appeared first on SpaceNews.